Patient selection for focal therapy

Authors:

Dr. med. Arnas Rakauskas

Dr. Massimo Valerio, MD, PhD, PD, MER

Lausanne University Hospital, CHUV

E-Mail: Arnas.Rakauskas@chuv.ch

Focal therapy is an attractive option for eligible patients with localised prostate cancer. A meticulous patient selection is the key to ensure high chances of oncological success and preservation of genito-urinary functions. In this article, we present the main considerations for selecting a candidate for focal therapy.

Keypoints

-

The eligibility for focal therapy is determined by an exhaustive diagnostic work-up.

-

The concordance between the MRI and biopsy results is the basis for focal therapy.

-

Informed consent and a will to follow close monitoring should be discussed with the patient prior to treatment.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second leading cancer in men worldwide and the most common solid malignity in Swiss men.1,2 Around 6600 new cases are diagnosed every year with 1300 deaths annually. Known risk factors are age, positive family history and race. Screening by means of regular PSA testing and digital rectal examination is recommended in well-informed men with prolonged life expectancy.3 In case of biochemical and/or clinical suspicion of disease, the current diagnostic pathway includes pre-biopsy prostate MRI followed by MRI fusion targeted and systematic prostate biopsy.

If localised disease is confirmed by biopsy, and metastatic spread is ruled out by relevant whole-body imaging, patients face a dilemma between interventional radical options and expectant management. Patient counseling relies upon assessment of risk of progression, patients’ comorbidities, and personal priorities. Presently, men with low-risk disease are offered active surveillance while men with intermediate to high-risk disease are offered radical treatment.

The standard whole-gland treatment options are radical prostatectomy and external beam radiotherapy. Both treatments lead to longer progression-free survival; however, the oncological benefit as compared to active surveillance is limited to men with very long life expectancy and/or with prostate cancer with aggressive features.4 Moreover, these standard treatments have a significant toxicity profile affecting mainly sexual and urinary functions which contributes to a decreased quality of life.5

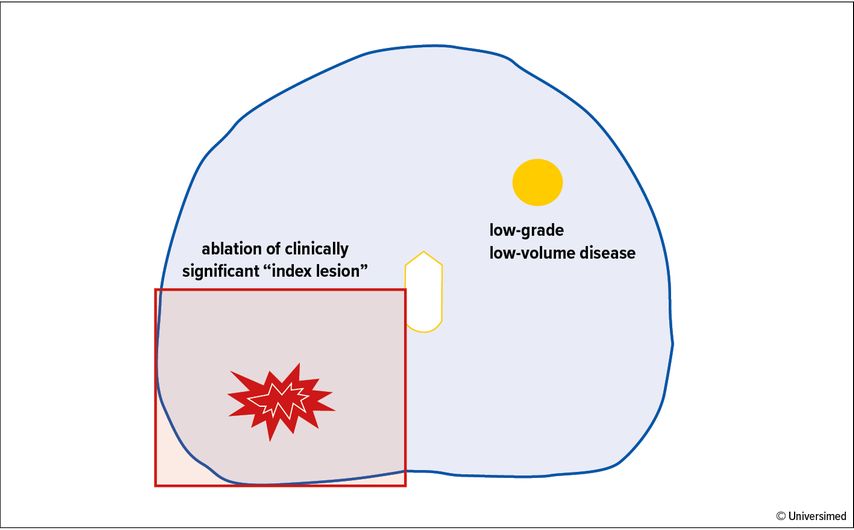

Abb. 1: Example of a focal therapy template showing a quadrant ablation of the “index lesion”. Note the presence of low-volume, low-grade disease on the contralateral side of the prostate which is left untreated and requires surveillance over time

Focal therapy (FT) is a tissue-preserving treatment strategy that has been gaining momentum over the last decade. The goal of FT is to successfully treat the disease while preserving quality of life. This is achieved by focal ablation of the area harbouring clinically significant disease within the prostate while preserving the rest of the gland.This approach allows to minimise the damage to the adjacent functional structures, namely the neuro-vascular bundles and the rhabdosphincter, which are essential to avoid sexual and urinary impairment, respectively, after treatment.

According to current evidence, FT should be offered to eligible informed patients diagnosed with intermediate-risk localised prostate cancer.6 While level 1 evidence shows that FT has very low toxicity compared to standard active treatments, long-term oncological outcomes are still awaited.

In our view, the key to success of a FT programme is rigorous patient selection. There are many factors that play an important role. These include an accurate diagnostic work-up, a good understanding of inherent features defining a good candidatefor FT, the availability of appropriate energy sources and the post-operative management.

Patient selection

Rationale for FT and initial diagnostic work-up

The adoption of prostate MRI and MRI fusion targeted biopsy has revolutionised the diagnostic pathway of prostate cancer by enhancing our ability to risk-stratify localised disease in terms of location, extension and aggressiveness. Previously, a systematic prostate biopsy was the standard diagnostic test, but its low negative predictive value resulted in an oversight of significant cancer lesions in up to 48%.7 Therefore, radical treatments were advised to most men, and tissue-preserving approaches could not be sought.

The introduction of prostate MRI has allowed a precise localisation of clinically significant lesions within the prostate.8,9 This shift in the diagnostic pathway from a random to a targeted approach has allowed FT to be considered as a valid treatment option. The rationale of FT is based on the fact that although prostate cancer is a multi-focal disease in most cases, the “index lesion”, namely the lesion with the most aggressive pattern, determines the natural history of the disease (Fig. 1).10 Consequently, in patients in which an index lesion can be determined, selective ablation of this lesion might not be inferior to radical treatment of the whole organ. This novel approach has been named FT.

A rigorous diagnostic work-up is required to define FT eligibility. A good quality prostate MRI that includes T2-weighted, diffusion weighted and dynamic contract-enhanced imaging must be performed prior to the biopsy. Prostate MRI should be reported by an experienced uro-radiologist according to PI-RADS or Likert classification system and accompanied by a visual synopsis as per international recommendations.11

The MRI should be followed by targeted and systematic or mapping prostate biopsy. This allows an accurate evaluation of the margins of the index lesion and rules out the presence of clinically significant non-MRI visible disease.8,12

Eligibility criteria

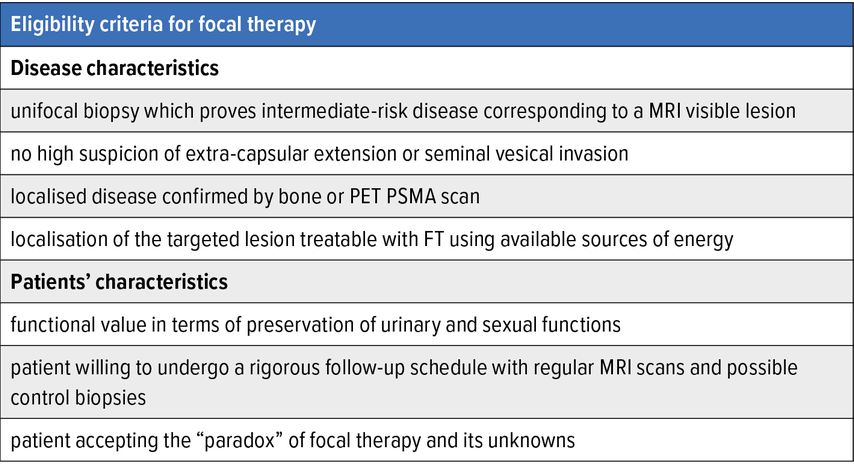

Eligibility criteria for FT are well established among experts (Tab. 1).

Biopsy-proven intermediate risk disease that corresponds to a visible MRI target is the ideal case. Satellite low-volume low-grade lesions deemed indolent or not significant can be left untreated without compromising patients’ oncological outcome.13 In contrast, FT should not be offered in case of a bilateral clinically significant disease. Also, the index lesion must be situated in an accessible region for the available FT modality.14 Moreover, the ideal candidate should not have a high clinical or radiological suspicion of extracapsular extension or seminal vesical invasion as FT is likely to fail in these cases. A bone scan or PET PSMA should be routinely performed to exclude metastases.

Every case should be discussed in a dedicated multi-disciplinary meeting, and patients must be informed about the knowns and unknowns related to FT. There should be functional value for the patient, as the goal of FT is not solely oncological but beyond in terms of urinary and sexual function preservation. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) need to systematically be used to assess these functions at baseline and after treatment. The baseline status is the most important predictor of functional outcomes following treatment.15

Choice of energy and treatment strategy

The choice of energy source should rely on patients’ characteristics and intrinsic features of the disease. The size and the location of the index lesion dictates the strategy and the energy source for FT.

Currently available technologies used for FT can be categorised into thermal and non-thermal energies.16 The most commonly employed thermal energies are high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), cryotherapy, and interstitial laser ablation. For the non-thermal sources of energy, the most used ones are photodynamic therapy, irreversible electroporation, and brachytherapy.

Each of these technologies has its own advantages and disadvantages. For instance, HIFU is ideal for lesions situated in the posterior part of the prostate. However, this treatment is not suitable to ablate lesions in the very anterior parts of the prostate as the ablation effect is limited by the distance from the treatment probe, which is usually positioned transrectally.

In contrast, cryotherapy, as other needle-based modalities delivered transperineally, can easily target lesions in anterior parts of the prostate but is difficult to control in the posterior parts due to the risk of rectal toxicity. Also, different sources of energy have different side effect profiles.17 Briefly, the specialist delivering the treatment must be aware of all these variables that play a significant role in order to choose the most appropriate modality.

There is no consensus on a maximum size of a lesion that could be treated by FT. A coverage with a minimum of 1cm margins around the index lesion should be envisaged to maximise local control since MRI is prone to understimate the actual extention of the disease.18 This type of margin might not be possible to achieve in patients with apical lesions that are situated next to the urinary sphincter, and therefore patients of this sub-group are not considered ideal candidates for FT because either the oncological or the functional outcome can be compromised. Some groups have proposed the use of non-thermal energies with reassuring results in this subgroup of patients, although external validation in controlled studies is pending.19

Informed consent and post-operative care

It is essential to inform the patient about the routine peri-operative care, mandatory follow-up, and possible complications.

Most treatments can be done in an outpatient setting with an indwelling catheter for 3–10 days after the procedure, depending on the protocol and the extent of ablation. Several consensus groups have defined the follow-up after FT. No international consensus group has been able to determine a consistent definition for biochemical failure after FT, concluding that multi-modal follow-up investigations are required to accurately diagnose patients with residual or recurrent disease in a timely manner.

Post-FT monitoring includes a PSA test every 3–6 months, an MRI at 6–12 months, followed by targeted biopsies to rule out residual disease. Afterwards, a PSA test every 6 months and yearly prostate MRI with “for cause” biopsy is deemed adequate by most groups; however, some still recommend mandatory biopsy at fixed time points, for instance after 3 and 5 years. The need for such monitoring after FT must be discussed with patients prior to treatment as this is part of the therapeutic strategy, such as in any tissue-preserving conservative approach.

Finally, as with any surgical intervention, complications can arise after FT.20 The more prostate tissue is treated, the more likely the patient will present complications. Most important patient-related factors that have an impact on treatment toxicity are the size of the prostate, previous pelvic and prostate surgery, and predisposing conditions (pre-existing erectile dysfunction, lower tract urinary symptoms and neurological comorbidities). The most common complications after FT usually occur within the first 30 days after the intervention. These are catheter-related issues and pain, haematuria, infectious complications, and lower urinary tract symptoms. We recommend providing an information leaflet for all patients explaining the possible post-operative complications in detail.

Final considerations

Patient selection for FT is key to success. Once disease characteristics are amenable to FT, patients’ priorities are usually the most important factor and will help to make the right therapeutic choice. Age and life expectancy also play an important role in the discussion. A young, healthy patient with clinically significant disease that meets all criteria for FT might still choose a radical treatment option considering possible recurrence in the future.

It is important to highlight that a recurrence of the disease after FT does not exclude the patient from a radical treatment option afterwards. It seems that the risk of post-operative complications following radical prostatectomy for treatment-naïve and FT treated patients is similar,21 although tissue scarring due to FT might deem the surgery more complex and advanced nerve preservation more challenging.

In contrast, an older patient is more likely to consider this approach, as the priority will most likely be to preserve quality of life and maintain disease control in a narrower time span. In summary, each case is individual, and a multi-disciplinary patient counselling is recommended to decide the most suitable therapeutic approach, FT being one of these with its own risk to benefit ratio.

Conclusion

FT is an attractive alternative to whole gland options for selected patients opting for active treatment. A rigorous diagnostic work-up is required to confirm the eligibility for this strategy. Patient counselling in a multi-disciplinary setting prior to treatment is recommended for a well-informed decision.

Literature:

1 Ligue contre le cancer Suisse: Le cancer de la prostate. Online unter https://www.liguecancer.ch/a-propos-du-cancer/les-differents-types-de-cancer/le-cancer-de-la-prostate . Abgerufen am 29.09.2022 2 Rawla P: Epidemiology of prostate cancer. World J Oncol 2019; 10: 63-89 3 Professionals S-O: EAU Guidelines: Prostate Cancer. Online unter https://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/#4 . Abgerufen am 24.3.2022 4 Hamdy FC et al.: 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1415-24 5 Resnick MJ et al.: Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. NEngl J Med 2013; 368: 436-45 6 Tay KJ et al.: Patient selection for prostate focal therapy in the era of active surveillance: an International Delphi Consensus Project. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2017; 20: 294-9 7 Ahmed HU et al.: Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet 2017; 389: 815-22 8 Kasivisvanathan V et al.: MRI-targeted or standard biopsy for prostate-cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1767-77 9 Simmons LAM et al.: The PICTURE study: diagnostic accuracy of multiparametric MRI in men requiring a repeat prostate biopsy. Br J Cancer 2017; 116: 1159-65 10 Ahmed HU: The index lesion and the origin of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1704-6 11 Grey ADR et al.: Multiparametric ultrasound versus multiparametric MRI to diagnose prostate cancer (CADMUS): a prospective, multicentre, paired-cohort, confirmatory study. Lancet Oncol 2022; 23: 428-38 12 Barzell WE, Melamed MR, Cathcart P, Moore CM, Ahmed HU, Emberton M et al.: Identifying candidates for active surveillance: an evaluation of the repeat biopsy strategy for men with favorable risk prostate cancer. J Urol 2012; 188: 762-7 13 Ahmed HU et al.: Focal ablation targeted to the index lesion in multifocal localised prostate cancer: a prospective development study. Eur Urol 2015; 68: 927-36 14 Sivaraman A et al.: Focal therapy for prostate cancer: an “à la carte” approach. Eur Urol 2016; 69: 973-5 15 Yap T et al.: The effects of focal therapy for prostate cancer on sexual function: a combined analysis of three prospective trials. Eur Urol 2016; 69: 844-51 16 Hopstaken JS et al.: An updated systematic review on focal therapy in localized prostate cancer: what has changed over the past 5 years? Eur Urol 2022; 81: 5-33 17 Emberton M: Has tailored, tissue-selective tumour ablation in men with prostate cancer come of age? BJU Int 2018; 121: 676-7 18 Le Nobin J et al.: Image guided focal therapy of magnetic resonance imaging visible prostate cancer: defining a 3-dimensional treatment margin based on magnetic resonance imaging-histology co-registration analysis. J Urol 2015; 194: 364-70 19 Blazevski A et al.: Focal ablation of apical prostate cancer lesions with irreversible electroporation (IRE). World J Urol 2021; 39: 1107-14 20 Rakauskas A et al.: Focal Therapy for Prostate Cancer: Complications and Their Treatment. Front Surg 2021; 8: 696242 21 Cathcart P et al.: Outcomes of the RAFT trial: robotic surgery after focal therapy. BJU Int 2021; 128: 504-10

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren:

Erhaltungstherapie mit Atezolizumab nach adjuvanter Chemotherapie

Die zusätzliche adjuvante Gabe von Atezolizumab nach kompletter Resektion und adjuvanter Chemotherapie führte in der IMpower010-Studie zu einem signifikant verlängerten krankheitsfreien ...

Highlights zu Lymphomen

Assoc.Prof. Dr. Thomas Melchardt, PhD zu diesjährigen Highlights des ASCO und EHA im Bereich der Lymphome, darunter die Ergebnisse der Studien SHINE und ECHELON-1

Aktualisierte Ergebnisse für Blinatumomab bei neu diagnostizierten Patienten

Die Ergebnisse der D-ALBA-Studie bestätigen die Chemotherapie-freie Induktions- und Konsolidierungsstrategie bei erwachsenen Patienten mit Ph+ ALL. Mit einer 3-jährigen ...