Evolving concepts in oligometastatic head and neck cancer

Author:

Petr Szturz, MD, PhD

Medical Oncology, Department of Oncology

University of Lausanne (UNIL) and Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV)

E-Mail: szturz@gmail.com

Characterised by an uncommon, indolent, and low-volume pattern of malignant dissemination to distant organs, the term oligometastatic has been used with the intent of local ablation and possibly improved overall survival in certain tumour types. But how uncommon is this phenomenon in head and neck cancer? What are the current treatment options and what the future directions of research? These and other questions will be addressed in this article.

Keypoints

-

An oligometastatic phenotype usually portends a better prognosis than widespread metastatic disease, but better understanding its biological background to optimize treatment is needed.

-

In head and neck cancer, oligometastatic recurrence seems to be more common in HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinomas, which has important implications for follow-up of cancer survivors after primary treatment.

-

According to patient- and disease-related factors, modalities of local ablation (metastasectomy, stereotactic body radiotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, and other) may complement or replace systemic therapy.

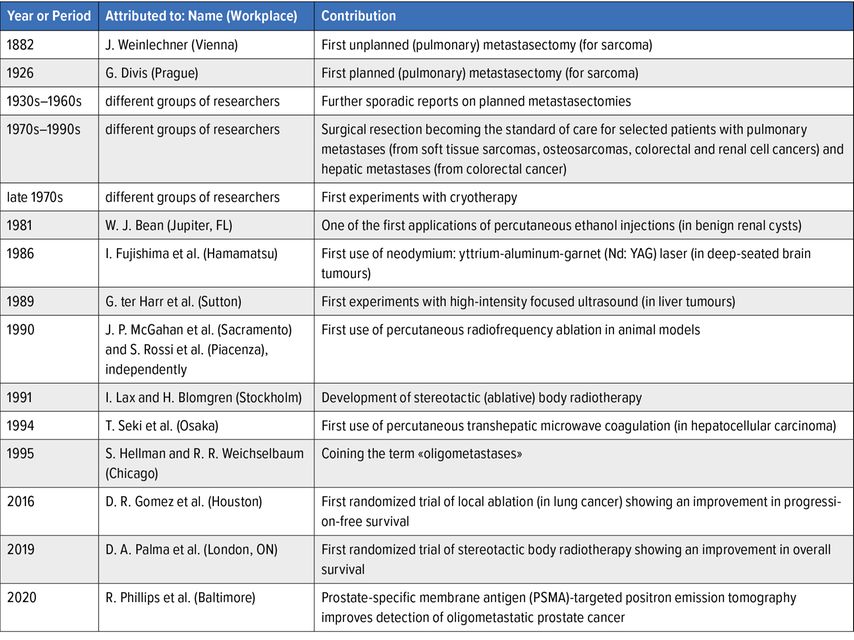

Being linked to the history of local ablation of distant metastases, our understanding of oligometastatic disease has evolved over time, and its definition has thus been a continuous matter of debate (Tab. 1).1–9 Clinical trials have usually adopted diagnostic criteria relying on the maximum number of metastases not surpassing three to five lesions, which has also been proposed in a recently published European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology/American Society for Radiation Oncology (ESTRO/ASTRO) consensus document.10

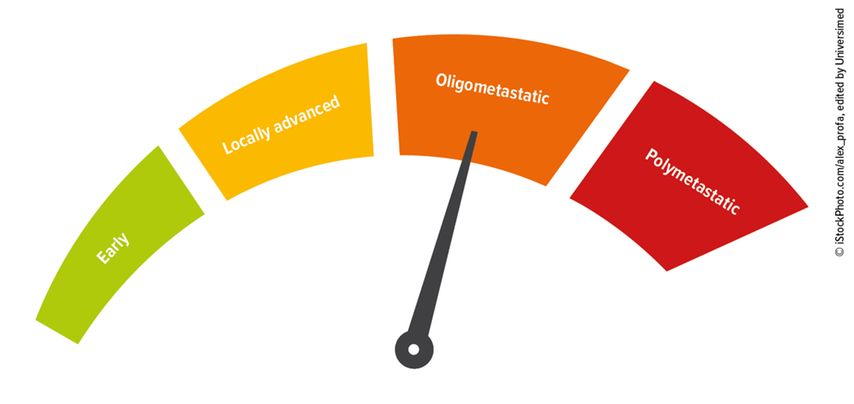

Nevertheless, mounting evidence suggests that a definition based primarily on a therapeutic opportunity has several shortcomings, particularly in that it does not exclude patients with a widespread subclinical dissemination. In this respect, disease biology and the role of the immune system seem to play a key role in the development of oligometastatic disease. This situation should therefore be considered a distinct clinical stage with intermediate aggressivity ranging between locoregionally advanced and widespread polymetastatic disease (Fig. 1), albeit more data being needed to draw definitive conclusions.

Fig. 1: An oligometastatic state can be considered an intermediate stage between locally or locoregionally advanced disease and widespread polymetastatic dissemination

Epidemiology

In squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN), the most common malignancy arising from the upper aerodigestive tract, reports on oligometastatic manifestation have been scarce and mostly limited to small retrospective studies.11 This scarcity can partially be attributed to an overall low prevalence of this condition.

Illustrative to that are the results of a large retrospective analysis: The investigators found that out of 934 patients with locoregionally advanced oropharyngeal cancer and known human papillomavirus (HPV) status, there were 15% presenting with distant recurrence after initial management with radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Only 4% of the 934 patients met criteria for oligometastatic disease defined by the presence of one to five lesions in not more than one organ. These patients were treated, and 10 (i.e., 1% of the initial population) were probably cured with no evidence of disease at the last follow-up visit (between 1.9 and 7.7 years after distant recurrence). All of the long survivors had lung disease, and the majority of them had HPV-positive disease treated with local ablation.12

These results have two important implications for clinical practice. The first is for patient follow-up, the latter for treatment, and both will be discussed here below.

Post-primary treatment surveillance

Early detection of recurrences, second primary tumours, and late toxicities in order to improve quality of life is the main objective of an active patient follow-up after completion of potentially curative treatment of the primary tumour with or without regional lymph node involvement (i.e., surgery, radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy). Because of limited evidence and lacking predictive factors, the impact of post-treatment surveillance on overall survival has not been unequivocally demonstrated.13 Therefore, apart from few specific situations, periodic imaging is not routinely recommended in SCCHN survivors. However, HPV-positive oropharyngeal carcinoma patients presenting with metachronous oligometastases in the lungs (i.e., more than 3–6 months after primary diagnosis) may be an exception because they can be cured; this should be kept in mind in daily practice.

Of note, dissemination in the lungs is typically asymptomatic, and in comparison with HPV-negative SCCHN, it may appear over a longer period of time and also later during the post-treatment follow-up, even after five years. In addition, multiple organ sites are often involved including unusual localisations (e.g., muscle, kidney, pancreas). Hence, if radiology surveys are carried out, they should cover extrapulmonary regions as well.

Local treatment

As evident from Table 1, surgical resection has been supported by the largest body of evidence. In a meta-analysis of eleven studies retrospectively evaluating pulmonary metastasectomy in 387 SCCHN patients, 5-year overall survival rate reached up to 29%. The most common clinical manifestation was a single metachronous lung nodule, although patients with up to six of them were included. Noteworthy, the included individual studies identified the following poor prognostic factors: primary tumour in the oral cavity, initial regional lymph node positivity, short disease-free interval after primary treatment, incomplete resection, and multiple nodules.14

Due to the encouraging results and non-invasive nature, stereotactic (ablative) body radiotherapy (SABR/SBRT) has emerged as a viable alternative, particularly in non-operable cases, however, a direct comparison with surgery has been lacking.11 Other, less frequently used methods of local ablation in SCCHN are mentioned in Table 1.

Systemic approaches

Systemic approaches are considered the current standard of care in recurrent and/or metastatic disease not amenable to curative local therapy. The latter condition varies according to institutional expertise and patient preferences. First-line palliative treatment options can be summarized as chemotherapy with or without cetuximab and immunotherapy with or without chemotherapy. They improve median overall survival to more than 1 year, but the outcomes strongly depend on used agents and patient and tumour characteristics.15 The information on the proportion of oligometastatic patients in the large phase III trials is missing, although it was probably low.

Nevertheless, similarly to local ablation, some patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors may experience long-lasting remission and this even if they initially presented with polymetastatic disease. Despite still limited long-term data, 5-year overall survival may be ranging from 10 to 30%.16,17 However, the major drawback is a lack of validated predictive markers, currently represented only by programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression.15

Further options

Combination of systemic and local approaches and their sequencing have been gaining growing interest of healthcare professionals. As an example, if systemic therapy decreases tumour burden down to several persisting lesions (oligopersistence), local ablation at the next step may be used for oligoconsolidation of these remaining metastases. Analogously, if few metastases start progressing in a patient with an otherwise controlled polymetastatic disease, local ablation may be used to selectively target this so-called oligoprogression. On the other hand, selected cases may benefit from local ablation in order to postpone the initiation of systemic treatment or a change thereof.11,18

Finally, keeping in mind that tumour doubling time is usually in the order of several months, treatment deferral may sometimes be preferred, especially in asymptomatic cases with known growth kinetics. The objective is to avoid jeopardizing quality of life or to verify if some micronodules develop in overt metastatic disease or not.11,19,20

Future directions and conclusions

Despite the long history of clinical experience with patients presenting with an oligometastatic phenotype, our knowledge of its different underpinnings is far from being complete. Thus, ample opportunities arise to conduct research in the areas of preclinical studies, diagnostic workup, and treatment. In particular, a better insight into its biological basis together with fine-tuning its clinical determinants is indispensable for developing reliable composite prognostic and predictive models.

The concept of oligometastatic disease pertains to many cancer types, especially lung cancer, where it became part of the latest TNM staging system, colorectal cancer, renal cell carcinoma, prostate and breast cancers, and sarcomas. Therefore, while some advances in this field are common to all entities, such as technological advances (e.g., improvements in external and internal radiotherapy) or innovative approaches to clinical trial design (e.g., adjusted endpoints, patient-reported outcomes), other advances are specific only to certain tumour types. These include PSMA-targeted PET/CT in prostate cancer, new drugs (e.g., epigenetic modifiers reversing a polymetastatic to an oligometastatic phenotype), combinations of local and systemic therapies (especially with immune checkpoint inhibitors), treatment sequencing, or liquid biopsy to monitor residual disease and detect early recurrence.18 The latter holds great promise also in HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma, where cell-free plasma HPV DNA has been in the forefront of experimental studies.21

In conclusion, a great leap forward in the management of recurrent and/or metastatic SCCHN has been made in the past 20 years. In the continuous process of improvement, research of oligometastatic disease occupies an important place, pursuing cure as the ultimate goal of oncology.

References:

1 van Dongen JA et al.: The surgical treatment of pulmonary metastases. Cancer Treat Rev 1978; 5: 29-48 2 Rusch VW: Pulmonary metastasectomy. Current indications. Chest 1995; 107: 322S-31S 3 Hughes KS et al.: Resection of the liver for colorectal carcinoma metastases: a multi-institutional study of patterns of recurrence. Surgery 1986; 100: 278-84 4 McGahan JP et al.: History of ablation. In van Sonnenberg E et al.: Tumor ablation. Springer 2005; 3-16 5 Lax I et al.: Stereotactic radiotherapy of malignancies in the abdomen. Methodological aspects. Acta Oncol 1994; 33: 677-83 6 Hellman S et al.: Oligometastases. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 8-10 7 Gomez DR et al.: Local consolidative therapy versus maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer without progression after first-line systemic therapy: a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 1672-82 8 Palma DA et al.: Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus standard of care palliative treatment in patients with oligometastatic cancers (SABR-COMET): a randomised, phase 2, open-label trial. Lancet 2019; 393: 2051-8 9 Phillips R et al.: Outcomes of observation vs stereotactic ablative radiation for oligometastatic prostate cancer: The ORIOLE phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2020; 6: 650-9 10 Lievens Y et al.: Defining oligometastatic disease from a radiation oncology perspective: An ESTRO-ASTRO consensus document. Radiother Oncol 2020; 148: 157-66 11 Szturz P et al.: Oligometastatic disease management: Finding the sweet spot. Front Oncol 2020; 10: 617793 12 Huang S et al.: Potential cure in HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer with oligometastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014; 90: S180-1 13 Szturz P et al.: Follow-up of head and neck cancer survivors: Tipping the balance of intensity. Front Oncol 2020; 10: 688 14 Young ER et al.: Resection of subsequent pulmonary metastases from treated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol 2015; 40: 208-18 15 Szturz P et al.: Translating KEYNOTE-048 into practice recommendations for head and neck cancer. Ann Transl Med 2020; 8: 975 16 Burtness B et al.: Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019; 394: 1915-28 17 Ferris R et al.: Nivolumab vs investigator‘s choice in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: 2-year long-term survival update of CheckMate 141 with analyses by tumor PD-L1 expression. Oral Oncol 2018; 81: 45-51 18 Szturz P et al.: Oligometastatic cancer: key concepts and research opportunities for 2021 and beyond. Cancers 2021; 13: 2518 19 Sacco A et al.: Current treatment options for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. JClin Oncol 2015; 33: 3305-13 20 Girard P et al: Oligometastases for clinicians: size matters. J Clin Oncol 2021; 39: 2643-6 21 Krasniqi E et al.: Circulating HPV DNA in the management of oropharyngeal and cervical cancers: current knowledge and future perspectives. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 1525

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren:

Erhaltungstherapie mit Atezolizumab nach adjuvanter Chemotherapie

Die zusätzliche adjuvante Gabe von Atezolizumab nach kompletter Resektion und adjuvanter Chemotherapie führte in der IMpower010-Studie zu einem signifikant verlängerten krankheitsfreien ...

Highlights zu Lymphomen

Assoc.Prof. Dr. Thomas Melchardt, PhD zu diesjährigen Highlights des ASCO und EHA im Bereich der Lymphome, darunter die Ergebnisse der Studien SHINE und ECHELON-1

Aktualisierte Ergebnisse für Blinatumomab bei neu diagnostizierten Patienten

Die Ergebnisse der D-ALBA-Studie bestätigen die Chemotherapie-freie Induktions- und Konsolidierungsstrategie bei erwachsenen Patienten mit Ph+ ALL. Mit einer 3-jährigen ...