Chloride in the spotlight – the hidden driver of acid-base homeostasis

Authors:

Dr. med. Patrick Hofmann1–3

Prof. Dr. med. Thomas Fehr4,5

1Division of Renal (Kidney) Medicine

Department of Medicine

Brigham and Women’s Hospital & Massachusetts General Hospital

Boston, Massachusetts

2Harvard Medical School

Boston, Massachusetts

3Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Boston, Massachusetts

4Department für Innere Medizin

Kantonsspital Graubünden, Chur

5Universität Zürich

Corresponding author:

Dr. med. Patrick Hofmann

E-Mail: phofmann@bwh.harvard.edu

Sie sind bereits registriert?

Loggen Sie sich mit Ihrem Universimed-Benutzerkonto ein:

Sie sind noch nicht registriert?

Registrieren Sie sich jetzt kostenlos auf universimed.com und erhalten Sie Zugang zu allen Artikeln, bewerten Sie Inhalte und speichern Sie interessante Beiträge in Ihrem persönlichen Bereich

zum späteren Lesen. Ihre Registrierung ist für alle Unversimed-Portale gültig. (inkl. allgemeineplus.at & med-Diplom.at)

Chloride is the most abundant extracellular anion and contributes fundamentally to osmolality, electroneutrality, and acid-base balance. Despite this central role, it has often received less attention in clinical practice compared with sodium or bicarbonate. Recent advances in physiology and clinical research underscore chloride’s role as a key regulator of acid-base balance and a practical guide for diagnosis and therapy.

Keypoints

-

Chloride is the major extracellular anion and a key determinant of acid-base balance. Even small shifts in serum chloride can substantially influence systemic pH.

-

In metabolic acidosis, chloride distinguishes between high anion gap (HAGMA) and normal anion gap (NAGMA) forms.

-

In metabolic alkalosis, urinary chloride helps separate chloride-responsive from chloride-resistant forms and guides therapy.

-

Renal chloride handling is segment-specific: proximally linked to bicarbonate reabsorption, and distally to bicarbonate secretion via the apical Cl–/HCO₃- exchanger pendrin.

-

Practical bedside tools include the serum anion gap, strong ion difference, urinary chloride, and the chloride-to-sodium ratio for differentiating and managing acid-base disorders.

The physiology of chloride in acid-base regulation

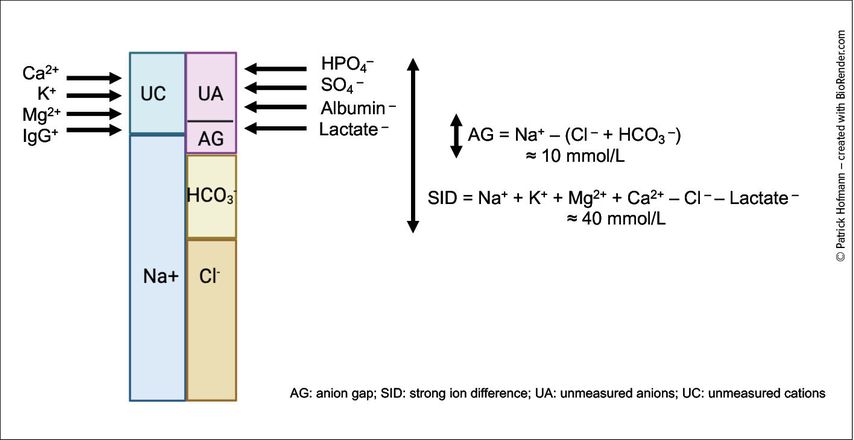

Chloride, as the dominant extracellular anion, has a direct influence on acid-base balance that goes beyond its traditional role as sodium’s counterpart. While the Henderson-Hasselbalch model describes pH regulation primarily through bicarbonate and pCO2, it does not fully capture chloride’s contribution. To address this, Peter Stewart introduced an alternative framework, the strong ion theory. In this model, pH is determined by three independent variables: pCO2, the total concentration of weak acids (mainly albumin and phosphate), and the strong ion difference (SID).1 Strong ions are defined as electrolytes that are completely dissociated at physiological pH and therefore exist in solution entirely as charged particles. The SID represents the difference between the sum of strong cations and the sum of strong anions:

SID=[Na+]+[K+]+[Ca2+]+[Mg2+]–[Cl–]–[lactate–]

Because chloride is the major strong anion in plasma, even small changes in its concentration can significantly affect the SID and thereby systemic pH. In clinical practice, sodium and chloride are the dominant determinants, so SID is often approximated as [Na+]–[Cl–]. A normal SID is about 40mmol/L. A fall in SID (typically due to a rise in chloride) lowers pH, while an increase in SID raises pH.

Within this framework, chloride is the predominant strong anion, and relatively small changes in serum chloride can substantially influence systemic acid-base balance. Figure 1 illustrates this with a “GambleGram”, which graphically balances serum cations (mainly sodium, plus potassium, calcium, magnesium) against anions (chloride, bicarbonate, proteins like albumin, and other anions). The difference between routinely measured cations and anions defines the anion gap (AG), while the difference between fully dissociated cations and anions represents the SID, both serving as tools to interpret acid-base disorders.

Fig. 1: “GambleGram” depiction of blood serum electrolytes. The total anion and total cation concentrations must be equal to maintain electroneutrality. The differences between these groups form the basis for calculating the anion gap (AG) and the strong ion difference (SID) (created with BioRender.com)

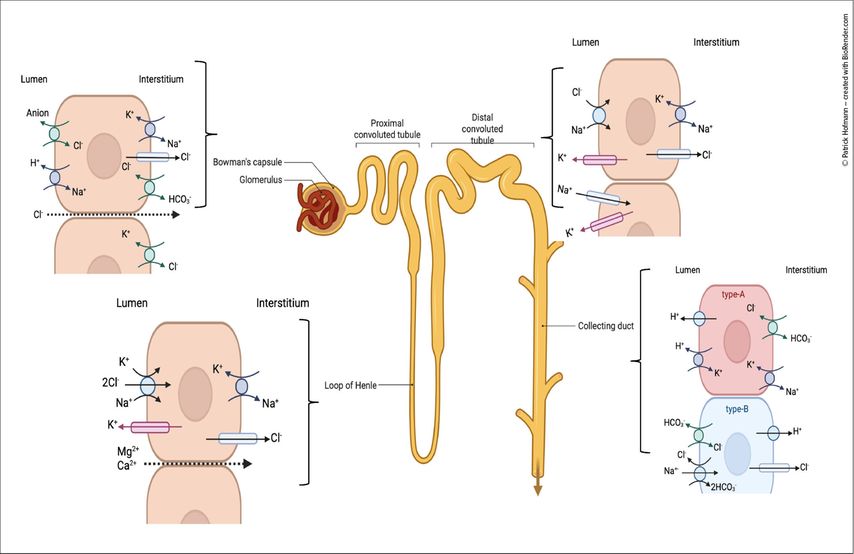

Renal handling of chloride

Approximately 99% of filtered chloride is reabsorbed along the nephron through segment-specific mechanisms. In the proximal tubule, chloride uptake occurs predominantly via paracellular pathways, supported by anion exchangers.2 In the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, the Na+-K+-2Cl– cotransporter (NKCC2) mediates chloride transport, serving as the target of loop diuretics. In the distal convoluted tubule, fine regulation is accomplished by the Na+-Cl– cotransporter (NCC), the site of action for thiazide diuretics.

In the collecting duct, intercalated cells play a central role: type A intercalated cells express the basolateral Cl–/HCO3- exchanger AE1, enabling bicarbonate reabsorption into the blood, whereas type B intercalated cells utilize the apical Cl–/HCO3- exchanger Pendrin to facilitate bicarbonate secretion into the tubular lumen.3 In addition, type B cells co-express the Na+-dependent Cl-/HCO3- exchanger (NDCBE), which provides chloride for pendrin and facilitates electroneutral bicarbonate secretion (Fig.2).4

Fig. 2: Chloride handling along the nephron. Schematic depiction of the chloride transporters in the proximal tubule, thick ascending limb of Henle, distal convoluted tubule and collecting duct (created with BioRender.com)

Beyond acid-base regulation, chloride contributes to key renal processes including tubuloglomerular feedback at the macula densa, modulation of renin release, and regulation of ammoniagenesis for acid excretion and bicarbonate generation, underscoring its central role in homeostasis.5

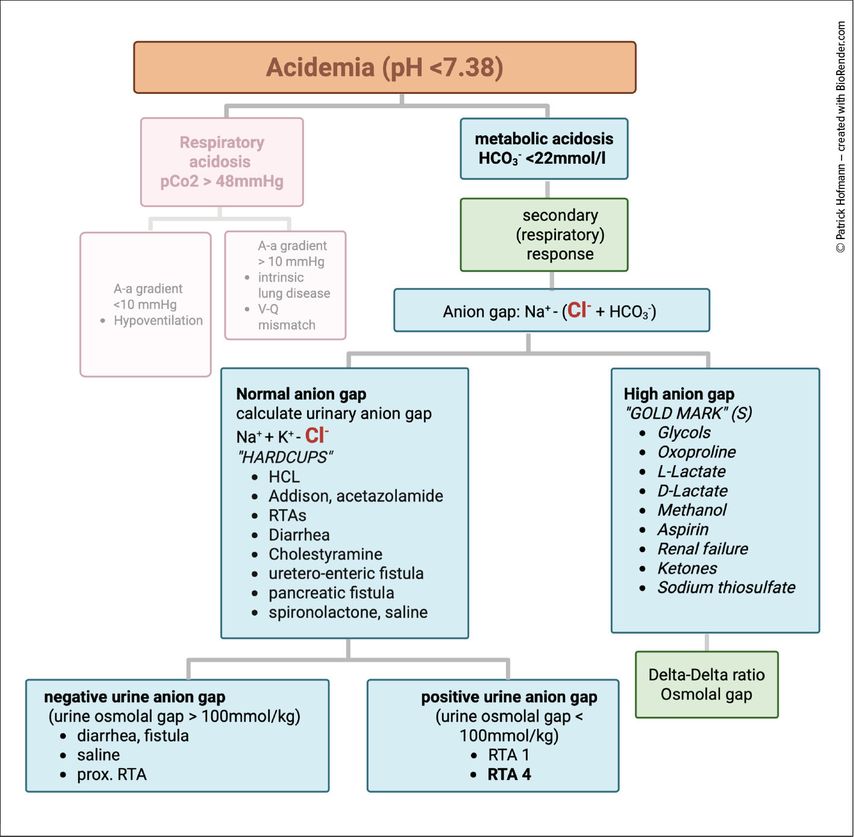

Chloride in metabolic acidosis

Metabolic acidosis is classically divided into high anion gap (HAGMA) and normal anion gap (NAGMA). Chloride is central to this distinction (Fig.3). In hyperchloremic acidosis (NAGMA), chloride rises to replace the lost bicarbonate, as seen in diarrhea, certain renal tubular acidoses, or following large-volume saline infusion. In HAGMA, by contrast, chloride remains normal or decreases while unmeasured anions accumulate.6

Fig. 3: Assessment of acidosis. Boxes in green are recommended additional steps. Secondary response refers to respiratory compensation of metabolic acidosis. Delta-Delta ratio is used to evaluate for combined acid-base disturbances, such as combined anion gap acidosis with combined normal anion gap acidosis (HAGMA-NAGMA) or HAGMA combined with metabolic alkalosis. An elevated osmolal gap in patients with HAGMA points towards toxic alcohol ingestion (created with BioRender.com)

The common acronym GOLDMARK summarizes the major causes of HAGMA: Glycols, Oxoproline, L-lactate, D-lactate, Methanol, Aspirin, Renal failure, and Ketones. As a personal modification, we add S for sodium thiosulfate, which is increasingly recognized as a cause of anion gap acidosis.

Different forms of HAGMA also resolve differently. In diabetic ketoacidosis, urinary loss of ketone anions represents an indirect bicarbonate loss, often leading to a secondary hyperchloremic acidosis during recovery.7 By contrast, lactic acidosis usually corrects more directly once the trigger is treated, as lactate can be metabolized back to bicarbonate.

The kidney responds to acidosis by enhancing acid excretion. In the proximal tubule, bicarbonate reabsorption and ammonium generation increase, while in the collecting duct, intercalated cells secrete protons via H+-ATPases and exchange basolateral bicarbonate for chloride, thereby maintaining electroneutrality.8

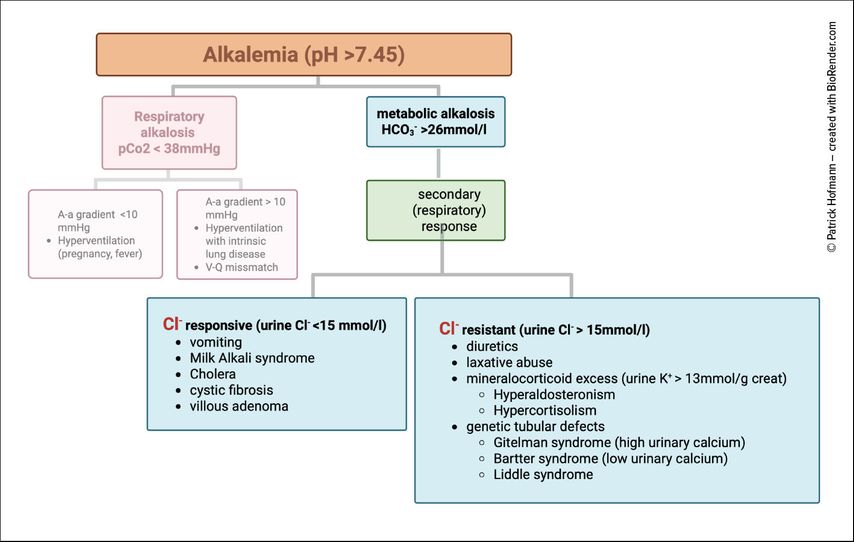

Chloride in metabolic alkalosis

Chloride also plays a central role in metabolic alkalosis. The key clinical distinction is between chloride-responsive and chloride-resistant forms (Fig.4)

In chloride-responsive alkalosis, typically due to vomiting or diuretic use, urinary chloride is low (<15mmol/L). Volume and chloride repletion with NaCl or KCl restores renal bicarbonate excretion and corrects the alkalosis.6

In chloride-resistant alkalosis, urinary chloride is elevated (>15mmol/L). Causes include mineralocorticoid excess, ongoing diuretic use, and genetic tubulopathies. In this setting, simple chloride replacement does not correct the disorder.9

Metabolic alkalosis is the most common acid-base disorder in hospitalized patients. Its persistence usually requires a “maintenance factor”, such as volume depletion, hypokalemia, hypochloremia, mineralocorticoid excess, or impaired kidney function. If left untreated, it is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, including diuretic resistance, impaired cardiac function, hypoventilation, and neuromuscular complications.10–13

The kidney corrects metabolic alkalosis by reducing proximal bicarbonate reabsorption and by distal secretion of bicarbonate. In the collecting duct, type B intercalated cells secrete bicarbonate via the apical Cl–/HCO3- exchanger pendrin, a process that requires adequate chloride delivery.4

Chloride as a diagnostic tool

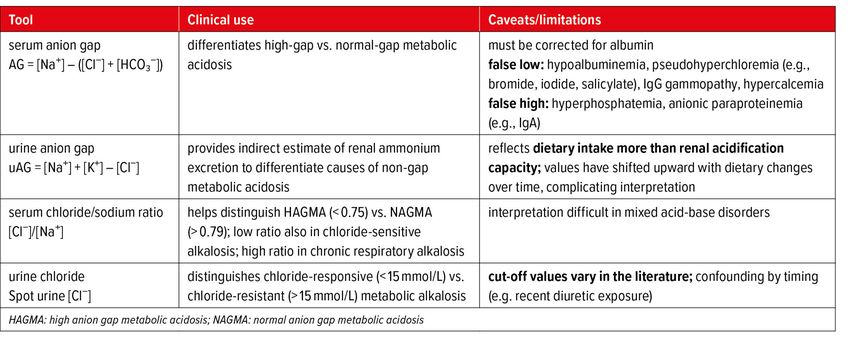

Beyond its physiological roles, chloride is a valuable marker in the assessment of acid-base disorders. The serum anion gap (AG) differentiates high-gap from normal-gap metabolic acidosis, while the urine anion gap (urine AG) provides indirect information about renal ammonium excretion. However, its accuracy is limited, as it is imprecise and strongly influenced by dietary factors.14,15 Direct measurement of urinary ammonium is preferred but often not available; in such cases, the urine osmolal gap can serve as an alternative surrogate. Urine chloride is the key test to separate chloride-responsive from chloride-resistant metabolic alkalosis. The chloride-to-sodium ratio can also provide diagnostic insight: values <0,75 suggest either a high anion gap metabolic acidosis (HAGMA) or a chloride-sensitive metabolic alkalosis, whereas values >0,79 are more consistent with a normal anion gap metabolic acidosis (NAGMA) or chronic respiratory alkalosis (Table 1).16

Literature:

1 Adrogué HJ et al.: Clinical approach to assessing acid-base status: physiological vs Stewart. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2022; 29: 343-54 2 Planelles G: Chloride transport in the renal proximal tubule. Pflügers Arch 2004; 448: 561-70 3 Soleimani M: The multiple roles of pendrin in the kidney. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 1257-66 4Do C et al.: Metabolic Alkalosis pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment: core curriculum 2022. Am J Kidney Dis 2022; 80: 536-51 5 Rein JL, Coca SG: “I don’t get no respect”: the role of chloride in acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal 2019; 316: 587-605 6 Ingelfinger JR et al.: Physiological approach to assessment of acid–base disturbances. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1434-45 7 Kamel KS, Halperin ML: Acid–base problems in diabetic ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 546-54 8 Palmer BF et al.: Renal tubular acidosis and management strategies: a narrative review. Adv Ther 2021; 38: 949-68 9 Palmer BF, Clegg DJ: Metabolic alkalosis treatment standard. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2024; 39: 1985-92 10 Trullàs JC et al.: The significance of metabolic alkalosis on acute decompensated heart failure: the ALCALOTIC study. Clin Res Cardiol 2024; 113: 1251-62 11 Testani JM et al.: Hypochloraemia is strongly and independently associated with mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Hear Fail 2016; 18: 660-8 12 Ter Maaten JM et al.: Hypochloremia, diuretic resistance, and outcome in patients with acute heart failure. Circ Hear Fail 2018; 9: 003109 13 Libório AB et al.: Increased serum bicarbonate in critically ill patients: a retrospective analysis. Intensiv Care Med 2015; 41: 479-86 14 Uribarri J, Oh MS: The urine anion gap: common misconceptions. J Am Soc Nephrol 2021; 32: 1025-8 15 Kraut JA, Madias NE: Serum anion gap: its uses and limitations in clinical medicine. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2: 162-74 16 Durward A et al.: The value of the chloride:sodium ratio in differentiating the aetiology of metabolic acidosis. Intensiv Care Med 2001; 27: 828-35

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren:

Die neue ADPKD-Guideline von KDIGO

Im Januar 2025 veröffentlichte KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) erstmals eine dezidierte Leitlinie zu Diagnostik und Therapie der autosomal-dominanten polyzystischen ...

Nierenkrebs – gegenwärtige Strategien und zukünftige Trends in der Therapie

Nichtklarzellige Nierenzellkarzinome (non-ccRCC) sollen zwar nach den gleichen Standards wie ccRCC behandelt werden, die Outcomes sind jedoch schlechter. Bei ccRCC hat sich die adjuvante ...

Prä- und postoperatives Transplantationsmanagement in der hausärztlichen Praxis

Hausärzte spielen in der Betreuung von Patienten vor und nach Nierentransplantation, aber auch bei der Begleitung von potenziellen Lebendspendern von der Auswahl bis zur Nachbetreuung ...