A call to action: addressing depression in cardiovascular guidelines

Authors:

Aliki Buhayer, BSc1,3

Dr. rer. medic. Kapka Miteva, PhD3

Prof. Dr. med. Edouard Battegay1,2

1,2International Center for Multimorbidity & Complexity in Medicine 1 Universität Zürich2 Merian Iselin Klinik, Basel3 Department of Cardiology Universität Genf

E-Mail: kapka.miteva@unige.ch

Vielen Dank für Ihr Interesse!

Einige Inhalte sind aufgrund rechtlicher Bestimmungen nur für registrierte Nutzer bzw. medizinisches Fachpersonal zugänglich.

Sie sind bereits registriert?

Loggen Sie sich mit Ihrem Universimed-Benutzerkonto ein:

Sie sind noch nicht registriert?

Registrieren Sie sich jetzt kostenlos auf universimed.com und erhalten Sie Zugang zu allen Artikeln, bewerten Sie Inhalte und speichern Sie interessante Beiträge in Ihrem persönlichen Bereich

zum späteren Lesen. Ihre Registrierung ist für alle Unversimed-Portale gültig. (inkl. allgemeineplus.at & med-Diplom.at)

Depression occurs more often in patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) than in the general population and worsens outcomes. Despite this, CVD clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) inconsistently address depression and rarely involve mental health specialists in their development. Providing physicians with systematic and comprehensive everyday clinical guidance for managing depression should be a priority in cardiovascular care.

Keypoints

-

Depression is highly prevalent in patients with cardiovascular disease and independently worsens outcomes.

-

Current CVD guidelines inconsistently address depression, and virtually none offers guidance on drug—disease interactions.

-

Routine screening and integrated management of depression can improve adherence, quality of life, and potentially cardiovascular outcomes.

-

Guideline committees should prioritize depression by systematically involving mental health specialists.

-

Clear guidance is also needed on polypharmacy, women’s health, and the management of multimorbid patients.

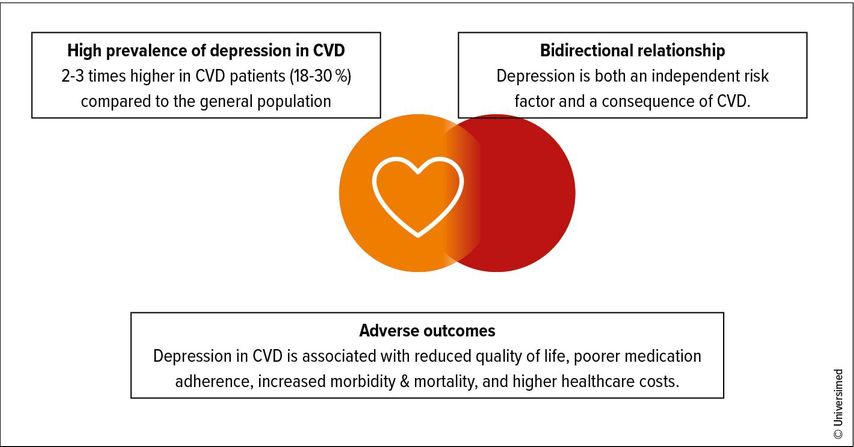

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 While advances in disease-specific management have substantially reduced mortality, longer life expectancy has also brought an increase in comorbidities. Among these, depression remains an important yet underrecognized condition. Mental health conditions, including depression, are among the leading causes of disability worldwide.2 In patients with CVD, its prevalence is two to three times higher than in the general population. Between 18% and 30% of patients with coronary artery disease live with depression, with even higher rates in heart failure (up to 40%) and post-stroke populations (up to 50% at five years).3–5 Women are disproportionately affected, with nearly double the prevalence compared to men. Beyond prevalence, depression independently predicts worse cardiovascular outcomes, resulting in increased hospitalizations, higher healthcare utilization, reduced quality of life, poorer treatment adherence, and higher mortality.6 Recent Mendelian randomization studies even suggest a causal relationship between depression and cardiovascular events, particularly coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and small-vessel stroke.7,8

Clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease: missing expertise and focus

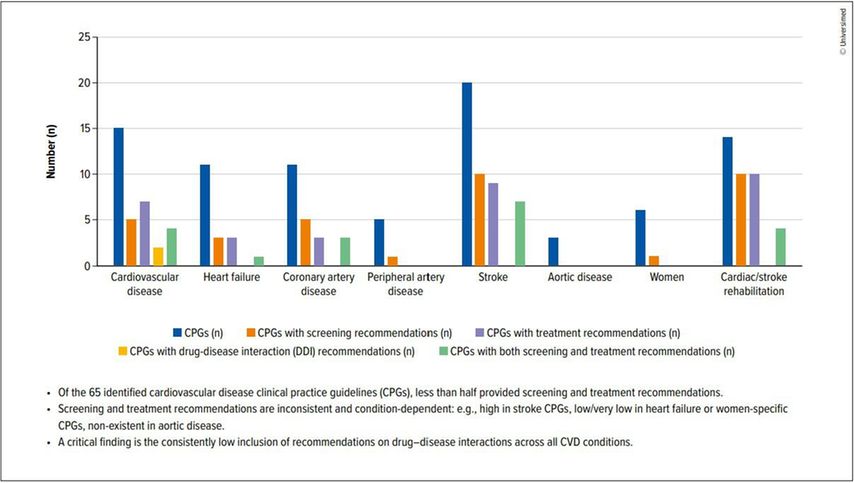

Clinical practice guidelines are designed to translate evidence into standardized, actionable recommendations. In areas such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidaemia, guideline-directed care has transformed outcomes. Yet, the picture is markedly different when it comes to depression in CVD (Fig.1).6 Our review of 65 CVD guidelines across five continents revealed a gap between recognition of depression as a risk factor (71%) and provision of guidance: Only 23% included both screening and treatment recommendations (37% screening; 34% treatment), fewer than 3% addressed drug–disease interactions, an important concern given the high prevalence of polypharmacy in this population. Notably, just 12% involved mental health specialists in their development.6 Entire CVD areas, such as peripheral artery disease (PAD) and aortic disease, were almost silent on the issue of depression (Fig.2).6 Where recommendations existed, they varied widely in scope, specificity, and evidentiary strength. Screening was often encouraged, typically using PHQ-2 or PHQ-9, but without practical advice on implementation.6 Treatment recommendations ranged from psychotherapy and physical activity to SSRI, yet supporting evidence was often graded as low to moderate.6 Few guidelines addressed drug–disease interactions, despite polypharmacy being common in this population.6 This lack of systematic, high-quality guidance perpetuates underdiagnosis and undertreatment, leaving clinicians uncertain and patients at risk (Fig.3).

Fig. 1: Depression & cardiovascular disease: a critical clinical challenge (see Armon DB et al. 2025)6

Fig. 2: Depression in clinical practical guidelines (CPGs): a frequently overlooked risk factor (see Armon DB et al. 2025)6

Fig. 3: Depression: a frequently overlooked condition in cardiovascular disease (CVD) guidelines (see Armon DB et al. 2025)6

Routine screening of depression in CVD patients: a healthcare priority

Integrating depression screening into structured care pathways improves adherence, mental health, and in some subgroups, cardiovascular outcomes. Arguments against routine depression screening in CVD often focus on the lack of proof of a definite impact on CVD outcomes. However, the clinical consequences of inaction are well documented, notably showing that depression

-

significantly increases 10-year CVD risk, particularly in women.

-

leads to poor adherence to guideline-directed medical therapy and reduced uptake of lifestyle interventions.

-

predicts higher rates of rehospitalization and emergency department visits.

-

contributes to reduced participation in cardiac rehabilitation, an intervention proven to improve outcomes.

Special populations & critical gaps

Three areas where guidance on depression management is particularly lacking deserve particular attention:

-

Women with CVD: Despite higher rates of depression, women are consistently underrepresented in cardiovascular trials, guidelines, and rehabilitation programs. Only one of six women-focused guidelines issues a recommendation for managing depression. This omission risks perpetuating poor outcomes for a population already facing inequities in cardiovascular care.6

-

Polypharmacy and drug interactions: Patients with CVD often take multiple medications. Yet few guidelines address drug–disease interactions between anti-depressants and cardiovascular therapies. The absence of practical recommendations for managing these risks is a serious limitation, particularly for multimorbid patients.6

-

Multimorbid patients: Most cardiovascular trials exclude patients with complex comorbidities. This leaves limited high-quality evidence to draw upon when formulating guidance for managing real-world patients, who rarely fit into single-disease silos. Without multimorbidity-focused guidance, clinicians are forced to navigate overlapping or even contradictory recommendations across specialities.6

A path forward for guidelines to address depression

PRACTICAL TIP

In daily practice, incorporate a brief screening tool for depression, such as the PHQ-2 or PHQ-9 during cardiovascular assessments.Among the strategies this systematic review proposed to guideline-issuing bodies for more effectively integrating depression into CVD guidelines was the development of a stand-alone guideline on depression, which CVD guidelines could then reference. The European Society of Cardiology’s timely publication of their clinical consensus statement on mental health and cardiovascular disease, published concurrently with this study, underscores and supports this strategy.9 This development highlights the growing recognition of mental health as an integral component of cardiovascular care and provides an authoritative reference point for future CVD guidelines to align with. Whichever approach is taken, involving mental health professionals in the guideline development process is essential. Structured, evidence-based, and implementable recommendations are urgently needed to align mental health care with the rigor applied to other cardiovascular risk factors.

Literature:

1 World Health Organisation (WHO): Cardiovascular diseases (CVD). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets ; zuletzt aufgerufen am 8.10.2025 2 World Health Organisation (WHO): Over a billion people living with mental health conditions – services require urgent scale-up. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-09-2025-over-a-billion-people-living-with-mental-health-conditions-services-require-urgent-scale-up ; zuletzt aufgerufen am 8.10.2025 3 Rafiei S et al.: Depression prevalence in cardiovascular disease: global systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2023; 13(3): 281-9 4 Freedland KE et al.: Prevalence of depression in hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure. Psychosom Med 2003; 65(1): 119-28 5 Ayerbe L et al.: Natural history, predictors, and associations of depression 5 years after stroke: the South London Stroke Register. Stroke 2011; 42 (7): 1907-11 6 Armon DB et al.: Depression and cardiovascular disease: mind the gap in the guidelines. Eur Heart J 2025; doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf479 7 Lu Y et al.: Genetic liability to depression and risk of coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and other cardiovascular outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc 2021; 10(1): e017986 8 de Geus EJC: Mendelian randomization supports a causal effect of depression on cardiovascular disease as the main source of their comorbidity. J Am Heart Assoc 2021; 10(1): e019861 9 Bueno H et al.: 2025 ESC clinical consensus statement on mental health and cardiovascular disease: developed under the auspices of the ESC clinical practice guidelines committee. Eur Heart J 2025; doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf191

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren:

Stellenwert der kardialen Bildgebung bei Kardiomyopathien

In einem Beitrag aus Österreich am diesjährigen europäischen Kongress für Kardiologie (ESC) wurde über das große diagnostische Potenzial der modernen kardialen Bildgebung und die ...

ESC-Guideline zur Behandlung von Herzvitien bei Erwachsenen

Kinder, die mit kongenitalen Herzvitien geboren werden, erreichen mittlerweile zu mehr 90% das Erwachsenenalter. Mit dem Update ihrer Leitlinie zum Management kongenitaler Vitien bei ...

ESC gibt umfassende Empfehlung für den Sport

Seit wenigen Tagen ist die erste Leitlinie der ESC zu den Themen Sportkardiologie und Training für Patienten mit kardiovaskulären Erkrankungen verfügbar. Sie empfiehlt Training für ...

_a%20frequently%20overlooked%20risk%20factor%20(see%20Armon%20DB%20et%20al.jpg)