Language use in a writing task in stress-related depression

Authors:

Dr. phil. Roberto La Marca, MSc. UZH1,2

Monika Scheiwiller, MSc1,2

Dr. med. Dipl. Theol. Michael Paff1

Dr. phil. Pearl La Marca-Ghaemmaghami2,3

Prof. Dr. med. Heinz Böker1,4

1Centre for Stress-Related Disorders

Clinica Holistica Engiadina SA

Susch

2 Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy

University of Zurich

3International Academy for Human Sciences and Culture

Walenstadt

4Psychiatric University Hospital

Department of Psychiatric Research

University of Zurich

Corresponding Author:

Prof. Dr. med. Heinz Böker

Psychiatric University Hospital

Department of Psychiatric Research

University of Zurich

Zurich, Switzerland

E-Mail: heinz.boeker@bli.uzh.ch

Vielen Dank für Ihr Interesse!

Einige Inhalte sind aufgrund rechtlicher Bestimmungen nur für registrierte Nutzer bzw. medizinisches Fachpersonal zugänglich.

Sie sind bereits registriert?

Loggen Sie sich mit Ihrem Universimed-Benutzerkonto ein:

Sie sind noch nicht registriert?

Registrieren Sie sich jetzt kostenlos auf universimed.com und erhalten Sie Zugang zu allen Artikeln, bewerten Sie Inhalte und speichern Sie interessante Beiträge in Ihrem persönlichen Bereich

zum späteren Lesen. Ihre Registrierung ist für alle Unversimed-Portale gültig. (inkl. allgemeineplus.at & med-Diplom.at)

Language can provide insight into an individual’s inner world. In the present study, we examined the language use in a short written description of the earliest childhood memory in inpatients with a stress-related depressive disorder compared to healthy controls. We found group differences, associations with perceived stress and depression severity, as well as changes in response to inpatient treatment.

Keypoints

-

Inpatients with a stress-related depressive disorder and healthy controls wrote a short text about their earliest childhood memory. The subsequent linguistic analyses of these written recollections revealed differences regarding the frequency of used pronouns and affective words.

-

In inpatients, higher perceived stress and depression severity was related to a lower use of positive emotion words, while higher depression scores were associated with a higher use of negative emotion words.

-

In a repetition of the writing task before the end of the treatment, linguistic analyses revealed a decrease in the amount of used negative emotion words.

Introduction

«Praise not a man before he speaketh, for this is the trial of men.» (Sirach 27:8). Researchers have been examining spoken and written language samples to get access to inner conditions of individuals, such as the experience of stress or a psychiatric disorder. With automatized text analysis programs (e.g. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count, LIWC),9 which include a dictionary and predefined allocations of the words to specific categories (e.g. ‘pronouns’ or ‘positive emotion words’), the analysis of language samples has become very easy.

In three non-clinical subsamples, Newell et al.8 examined the association between stress and a variable called “depressed language”, which was composed by three LIWC cateogories: higher use of ‘1st person singular pronouns’, higher use of ‘negative emotions’, and lower use of ‘positive emotions’. The authors found a significant (or at least a trend towards significance) positive association between chronic (Perceived Stress Scale, PSS) or acute stress (single items) and “depressed language” used in a structured 45min long interview (study 1), a 5min speech task (study 2), and a speech task “likely to induce acute stress and uncertainty” (study 3). In a study examining depressed and never-depressed undergraduates, the former group revealed significantly more ‘1st person singular words’ and ‘negative emotion words’, and slightly fewer ‘positive emotion words’ in a 20min writing task.10 In line with Rude et al.,8 a meta-analysis about the association between depression and ‘1st person singular pronouns’ revealed a small correlation (r=.13).4

The aims of the present analyses were to examine, first, differences between inpatients with a stress-related depressive disorder and healthy controls with regard to pronouns and emotion words used in a writing task, second, the association of perceived stress and depression severity with these word categories in inpatients, and third, the effect of a multimodal inpatient treatment on language use.

Methods

Subjects and study design

This study is part of a larger research project examining healthy controls (HC) and inpatients with stress-related depressive (or adjustment) disorders treated at a specialized clinic for stress-related mental disorders (i.e., the Clinica Holistica Engiadina SA, Susch, Switzerland), which follows recommendations for the multimodal treatment of clinical burnout.5 The inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as the final sample characteristics have been previously described.6

While HC were examined only once, inpatients participated twice, after starting (T1) and before terminating (T2) the inpatient treatment. Additionally, some questionnaires were distributed at 6 months follow-up (T3). This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Canton of Zurich. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The Clinica Holistica Engiadina funded this study.

Psychometric measures

Depression severity was assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II)1 at T1, T2, and T3. Additionally, the clinician-administered Hamilton Depression scale (HAMD-17)2 was assessed at T1 and T2. Perceived stress was measured using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)3 at T1 and T3.

Word use

Writing task

Participants were instructed to recall their earliest childhood memory. After 3 minutes of preparation, they were offered 4 minutes to write down this memory on a laptop. In inpatients, this task was conducted twice, at T1 and T2, while HC participated only once.

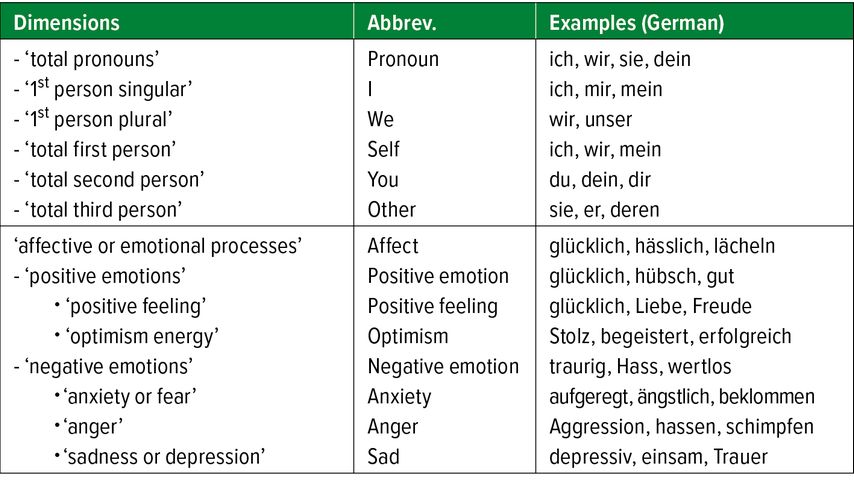

Linguistic analysis

The linguistic analysis was conducted using the German adaptation of the LIWC,12 a program which calculates the percentage of words used in a text regarding predefined word categories. We limited the LIWC analyses a priori to the (sub)categories listed in table 1.

In line with recommendations ( https://www.liwc.app/help/howitworks ), we considered only texts with at least 50 words.

Data analyses

IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 for Macintosh (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) was used for the statistical analyses. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check for violations of the assumption of normal distribution. Concerning differences between inpatients and HC or between linguistic data at T1 and T2, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied. To analyse associations between variables, Pearson’s product-moment (r) or Spearman rank-order correlations (rs) were conducted. All analyses were one-tailed and the level of significance was set at p <.05.

Results

Thirty-nine inpatients with a stress-related depressive disorder and 21HC participated in the present study. Four inpatients had to be excluded based on the exclusion criteria.6 Of the remaining participants, texts that did not reach the minimum word count (see Linguistic analysis) led to an exclusion of two HC (final nHC=19), three inpatients at T1 (n inpatients, T1=32), and three further inpatients at T2 (ninpatients,T2=29).

Group differences at treatment onset

When comparing the inpatients with the HC, aside from the expected differences with regard to stress and depression,6 the former revealed a significant higher use of ‘total second person’ pronouns (U=235.500; p=.027) and ‘anger’ words (U=210.000; p=.003), and a significant lower use of ‘optimism energy’ words (U=199.500; p=.011) (see table 1). All other variables did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Association between word categories and symptoms in inpatients

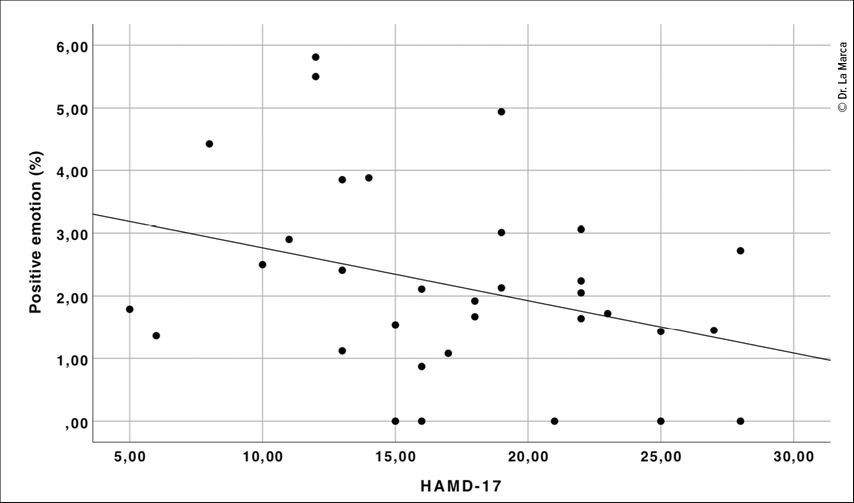

At T1, inpatients BDI-II scores were positively related to the use of ‘negative emotion’ words (rs=.36, p=.020), and ‘anger’ words (rs=.38, p=.015). The HAMD-17 was inversely correlated with the use of ‘positive emotion’ words (r=-.35, p=.024; Fig. 1), while the PSS was negatively correlated with the use of ‘positive feeling’ words (rs=-.63, p<.001). All other associations were not significant.

Fig. 1: Association between the HAMD-17 score and the LIWC category ‘positive emotions’ in inpatients at T1

Differences between language use at T1 and T2

Some inpatients described another childhood memory at T2 as compared to T1. Analyses revealed a significant decrease in the use of ‘anxiety or fear’ words (z=-1.753, p=.040, n=29) and ‘sadness or depression’ words (z=-1.804, p=.036, n=29), while the other categories did not differ significantly.

Discussion

The present study aimed at examining associations between stress, depression and word use in a writing task, as well as the effect of an inpatient treatment on language use. Inpatients used more ‘total second person’ pronouns and ‘anger’ words, but less ‘optimism energy’ words as compared to HC. In inpatients, perceived stress was related to a less frequent use of ‘positive feelings’ at T1, while depression severity correlated negatively with the use of ‘positive emotion’ words and, additionally, positively with the use of ‘negative emotion’ and ‘anger’ words. Interestingly, inpatients revealed a significant decrease in the use of ‘sadness or depression’ and ‘anxious or fear’ words when repeatedly describing their earliest childhood memories at T2 compared to T1.

The present comparison between the inpatients and HC yield a significant higher use of ‘total second person’ pronouns and ‘anger’ words, but a lower use of ‘optimism energy’ words in inpatients. This is in contrast with the literature reporting a higher word use of ‘I’10 and partially in line with studies reporting more ‘negative emotion’ words in depressed individuals. One explanation is that we examined a specific sample of depressed subjects, namely those clearly related to stress or burnout, and not depressed subjects in general. Hochstrasser et al.5 list aggression and irritability as typical symptoms of burnout, while depersonalisation as one of three typical characteristics of burnout includes a cynical and negative attitude towards clients or others.7

When focussing on the inpatients, perceived stress was inversely related to the use of positive emotion words. This is in line with the findings from Newell et al.,8 who more generally found a significant association with “depressed language”, which among other things included a lower use of ‘positive affect’ words. In line with Rude et al.,10 we found depression to be related to a lower frequency of ‘positive emotion’ words.

The findings in our study showed a decrease in ‘sadness or depression’ and ‘anxiety or fear’ words in inpatients in response to the treatment, both being two prominent symptoms of depression and/or burnout.1,5 Therefore, it can be assumed that the specialized inpatient treatment was effective not only in decreasing symptoms of stress and depression,6 but also in reducing implicit indicators of the psychopathology.

In general, it remains unclear, whether the differences between the groups emerged because inpatients were exposed to more adverse childhood experiences,11 have a bias to recall more negative memories, and/or remember events more negatively.

Despite the small sample size, the short lengths of the texts, and the specificity of the memory content used in the present study, the findings are noteworthy, revealing language analyses to be of potential benefit for the evaluation of disease severity and treatment impact.

Acknowledgment

We thank all participants, the team of the Clinica Holistica Engiadina and interns at the University of Zurich for the support during the time of data collection. We would like to thank the Clinica Holistica Engiadina for funding the study and for allowing data collection.

Conflict of interest

RL and MS started working at the Clinica Holistica Engiadina only after the study began. MP is the head doctor and medical director at the Clinica Holistica Engiadina. HB is part of the Scientific Advisory Council Board of the Clinica Holistica Engiadina as well as a clinical supervisor at the clinic. The Clinica Holistica Engiadina did not have any influence on the selection of the analyses nor on the manuscript.

Author contributions

HB and RL acquired the funding. RL and HB conceptualized the study. RL and PLG defined the methods. RL, MS and HB planed, and MS conducted the investigation. RL and MS concluded data curation. RL conducted the analysis. RL wrote the original draft. MS, MP, PLG, and HB reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Clinica Holistica Engiadina, Switzerland, funded this study, which was conducted at the Clinica Holistica Engiadina. The views expressed are solely those of the authors. They do not reflect the official policy or position of the CHE.

Data Availability Statement

Participants did not give consent to share their data. Therefore, data is confidential and not available.

Literature:

1 Beck AT et al.: Beck-Depressions-Inventar (BDI–II, dt. Version: Hautzinger M et al.: (2. Aufl.). Frankfurt: Pearson Assessment, 2009 2 CIPS, 1977. Internationale Skalen für Psychiatrie. Beltz Test, Weinheim 3 Cohen S et al.: A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385-96 4 Edwards TM, Holtzman NS: A meta-analysis of correlations between depression and first person singular pronoun use. Journal of Research in Personality 2017; 68: 63-8 5 Hochstrasser B et al.: Burnout-Behandlung Teil 2: Praktische Empfehlungen. Swiss Medical Forum – Schweizerisches Medizinforum 2016; 16, 561-6 6 La Marca et al.: The role of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism in the inpatient treatment of stress-related depressive disorders. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders 2022; 6: 142-61 7 Maslach C, Jackson SE: The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behaviour 1981; 2: 99-113 8 Newell E et al.: You sound so down: capturing depressed affect through depressed language. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 2018; 37: 451-74 9 Pennebaker JW et al.: Linguistic inquiry and word count – LIWC2001. Mahwah: Erlbaum, 2001 10 Rude SS et al.: Language use of depressed and depression-vulnerable college students. Cognition and Emotion 2004; 18: 1121-33 11 Sahle BW et al: The association between adverse childhood experiences and common mental disorders and suicidality: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2022; 31: 1489-99 12 Wolf M et al.: Computergestützte quantitative Textanalyse: Äquivalenz und Robustheit der deutschen Version des Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count. Diagnostica 2008; 54: 85-98

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren:

Therapeutisches Drug-Monitoring (TDM) in der Neuropsychopharmakologie: von der Theorie zur klinischen Routine

Therapeutisches Drug-Monitoring (TDM) verbindet angewandte Pharmakokinetik mit der klinischen Praxis und stellt damit ein wertvolles Instrument der Präzisionsmedizin dar. Absorption, ...

Neuropsychologische Profile des Autismus im Erwachsenenalter: Kriterien im Hinblick auf gutachterliche Verfahren

«Hochfunktionale» Autist:innen wie Asperger-Autist:innen können trotz ihres Leidensdrucks ein unauffälliges Dasein führen. Dies kann sich sowohl in unauffälligen neuropsychologischen ...

Ketamin-augmentierte Psychotherapie

Das schnell wirksame Antidepressivum (S-)Ketamin wird bei therapieresistenten Patient:innen effektiv eingesetzt. Als zentrale Komponente eines biphasischen Wirkmechanismus wird für ...