Management of chronic insomnia according to the latest European guidelines

Author:

Mauro Manconi, MD, PhD

Head of Sleep Medicine Unit

Neurocenter of Southern Switzerland

Regional Hospital of Lugano, EOC

Lugano

Department of Neurology

University of Bern

Università della Svizzera Italiana

E-Mail: mauro.manconi@eoc.ch

Sie sind bereits registriert?

Loggen Sie sich mit Ihrem Universimed-Benutzerkonto ein:

Sie sind noch nicht registriert?

Registrieren Sie sich jetzt kostenlos auf universimed.com und erhalten Sie Zugang zu allen Artikeln, bewerten Sie Inhalte und speichern Sie interessante Beiträge in Ihrem persönlichen Bereich

zum späteren Lesen. Ihre Registrierung ist für alle Unversimed-Portale gültig. (inkl. allgemeineplus.at & med-Diplom.at)

Insomnia is among the most prevalent sleep disorders, affecting up to one third of adults and 6–10% with chronic forms. The 2023 European Insomnia Guidelines1 emphasize that insomnia is an independent disorder rather than a secondary symptom, as it may itself contribute to depression, cardiometabolic, and neurodegenerative diseases. Swiss data confirm a growing prevalence, particularly in the range of age between 15 and 30 years. Diagnosis relies primarily on clinical evaluation supported by sleep diaries and actigraphy. In selected cases, laboratory tests or polysomnography are indicated to exclude secondary causes, especially in refractory cases. The first-line treatment for chronic insomnia remains cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), with sustained benefits over time. Pharmacotherapy is reserved for short-term adjunctive use, following evidence-based recommendations. A major innovation is the approval of daridorexant, a dual orexin receptor antagonist (DORA) promoting physiological sleep with low risk of dependence.

Keypoints

-

The 2023 European Insomnia Guidelines redefine insomnia as an independent disorder, abandoning the distinction between primary and secondary forms.

-

Chronic insomnia is both a consequence and a cause of somatic and psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease.

-

In Switzerland, the prevalence of insomnia symptoms is steadily increasing, especially among adolescents (“techno-insomnia”) and elderly adults.

-

Diagnosis should be based on clinical evaluation, sleep diary, and actigraphy; melatonin rhythm and thyroid profile may support differential diagnosis.

-

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) – face-to-face, group, or digital – remains the first-line treatment for all adults.

-

Novel pharmacological options include dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORA), such as daridorexant, effective and approved in Switzerland.

Definition and classification

According to the ICSD-3-TR (International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd Edition, Text Revision), insomnia disorder is characterized by one or more of the following: difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, early morning awakening with inability to return to sleep, accompanied by daytime impairment such as fatigue, reduced concentration, mood alteration, or decreased performance. Insomnia becomes chronic when symptoms occur at least three times per week and persist for at least three months despite adequate opportunity and conditions for sleep. The 2023 update emphasizes that insomnia is not simply a symptom, but a distinct disorder that can coexist with other medical or psychiatric diseases. Nowadays, the definition of insomnia reported in the last edition of the ICSD-3-TR coincides with the one of the DSM-5.

From “primary” and “secondary” to a unified concept

In earlier classifications, insomnia was divided into primary and secondary forms, depending on whether another condition explained the complaint. This dichotomy has now been abandoned. Modern research has shown that insomnia itself may contribute causally to disorders such as depression, hypertension, cardiometabolic dysfunction, and even neurodegenerative processes.

Long-standing insomnia alters hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulation, increases inflammatory markers, and triggers cortical hyper-arousal. In chronic cases, it becomes clinically meaningless to determine “what came first”; the practical goal is to treat insomnia as an active disorder deserving its own management plan.

Epidemiology and prevalence

In the general adult population, the prevalence of insomnia symptoms ranges from 25–30%, while chronic insomnia disorder affects 6–10% of adults in Europe. Women are affected more frequently than men, particularly during peri- and post-menopausal years. Risk increases with age, psychological stress, shift work, and comorbid medical illness. Despite its prevalence, sleep medicine remains poorly represented in undergraduate and postgraduate curricula. In Switzerland, only a limited number of medical schools provide structured training in sleep disorders. This gap contributes to underdiagnosis and undertreatment, especially in primary care. Promoting sleep medicine education and collaboration between general practitioners, neurologists, and psychiatrists is essential for early identification and management.

Trends in Switzerland

Data from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (Bundesamt für Statistik, BFS)2 and recent national health surveys show a progressive rise in sleep complaints over the last decade. Between 2010 and 2023, the proportion of adults reporting poor or insufficient sleep increased from 27% to over 35%. Contributing factors include longer working hours, digital device use, and psychological distress following the Covid-19 pandemic. Among adolescents, the so-called “techno-insomnia” – difficulty falling asleep or maintaining regular schedules due to late-night smartphone and screen exposure – has become a recognized public health issue. Insomnia in adolescents has been proved a risk factor for depression and suicidal thoughts.

Clinical assessment

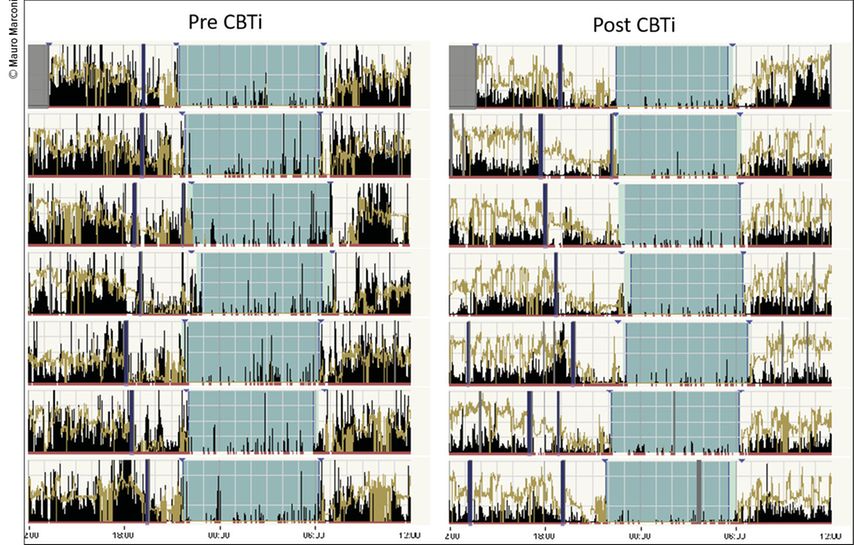

A thorough clinical interview remains the cornerstone of diagnosis. The clinician should explore: sleep habits and schedule (bedtime, wake time, naps), environmental factors (noise, light, partner behavior), lifestyle factors (caffeine, alcohol, medications, screens), comorbid conditions (pain, mood, respiratory, neurologic, endocrine). Severity of insomnia might be evaluated with the validated and self-administered Insomnia Severity Scale. Patients should complete a sleep diary for at least two weeks. When available, actigraphy provides an objective estimation of rest-activity cycles, sleep efficiency, and circadian regularity, especially useful in distinguishing insomnia from circadian rhythm disorders (Fig.1). Identifying the chronotype (morningness–eveningness) is crucial to exclude circadian rhythm disorders such as delayed sleep-wake phase disorder.

Fig. 1: One week actigraphy recording in a 42 year old woman affected by chronic insomnia naÏve for pharmacological therapy. Left: basal recording before any intervention. Right: follow-up recording performed after a full section (8 weeks) of group cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), showing a significant improvement of sleep continuity

If the diagnosis remains uncertain, the salivary melatonin profile (dim-light melatonin onset, DLMO) can be used to assess biological timing, though it is not routinely necessary. Basic blood work may include a thyroid function profile, as hyperthyroidism can mimic or aggravate insomnia. If clinical suspicion arises, screen for iron deficiency (restless legs syndrome), renal, hepatic, or inflammatory abnormalities.

Insomnia may coexist with or be secondary to other sleep disorders. The interview should always include targeted questions on: restless legs syndrome, sleep apnea, parasomnias included REM behavior disorder.

Polysomnography (PSG) is not routinely indicated in typical chronic insomnia, but should be considered when insomnia is refractory to first-line therapy, red flags are present (violent movements, apnea suspicion, periodic limb movement disorder [PLMD], narcoleptic features), or diagnostic uncertainty persists.

Pathophysiological concepts: hyperarousal

Modern neurophysiological research describes chronic insomnia as a state of 24-hour hyperarousal, characterized by: increased high-frequency EEG activity during non-REM sleep, elevated sympathetic tone and cortisol levels, reduced heart-rate variability, heightened functional connectivity in arousal networks. This framework has guided the development of new pharmacological classes acting on the orexin/hypocretin system, central to wake maintenance.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I)

CBT-I remains the first-line therapy for chronic insomnia according to the European Insomnia Guidelines,1 independent of age or comorbidities. It aims to reduce maladaptive behaviors and counteract cognitive hyperarousal through structured techniques: stimulus control, associate bed only with sleep and intimacy; sleep restriction therapy, temporarily limit time in bed to improve sleep efficiency; cognitive therapy, challenge catastrophic beliefs about sleep; relaxation techniques, breathing, mindfulness, progressive muscle relaxation; sleep hygiene education.

CBT-I can be delivered individually, in group sessions, or via digital/virtual platforms (e-CBT-I), which have shown comparable efficacy in randomized controlled trials (RCT). A landmark RCT demonstrated that an online CBT-I program significantly improved sleep efficiency and reduced insomnia severity compared with placebo and pharmacotherapy arms.3 Benefits often persist for months to years, exceeding the durability of hypnotic drugs.

Pharmacological therapy

Pharmacotherapy is reserved for short-term adjunctive use when CBT-I is unavailable, insufficient, or when rapid relief is required. According to the European Insomnia Guidelines:1 Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (zolpidem, zopiclone) may be used for ≤4 weeks, at the lowest effective dose. Melatonin prolonged release 2mg is indicated in adults ≥55 years for up to 3months. Sedative antidepressants (e.g., low-dose doxepin, trazodone) may be considered in selected cases with comorbid depression, though evidence is weaker. Antipsychotics, antihistamines, and herbal remedies are not recommended due to limited efficacy and safety concerns.

Novel therapies: dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORA)

A major pharmacological innovation is the class of dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORA), targeting the orexin-1 and orexin-2 receptors that sustain wakefulness (Fig.2). By selectively inhibiting these pathways, DORA promote physiological sleep without altering sleep architecture or inducing rapid dependence. Daridorexant, the first DORA approved in Switzerland, has shown robust efficacy and favorable tolerability in large RCT.4 At doses of 25–50mg nightly, it significantly improved sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset, and daytime functioning, with minimal residual effects the next morning. Unlike traditional hypnotics, daridorexant does not suppress REM sleep and carries a low risk of tolerance or withdrawal. Common adverse events are mild (headache, fatigue, somnolence). The medication is contraindicated in narcolepsy and should be used with caution in severe hepatic impairment. RCTs comparing daridorexant to placebo and zolpidem confirm its superior benefit-risk balance, especially in older adults, supporting its inclusion as a recommended option in the European guidelines (moderate-strong recommendation).

Fig. 2: Orexinergic arousal network and DORA mechanism of action. Left: Lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons (green) project to arousal-promoting nuclei – the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN; histamine), locus coeruleus (LC; norepinephrine), dorsal raphe nucleus (DR; serotonin), pedunculopontine nucleus (DPT; acetylcholine) – and cortex. Right: At the orexin synapse, activation of OX1R and OX2R increases postsynaptic excitability and promotes wakefulness; dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORA) competitively block OX1R/OX2R, preventing orexin A/B binding and thereby reducing postsynaptic excitability to promote sleep

Integrative and preventive perspective

For the general practitioner, managing insomnia means:

-

Recognize it early through open questioning about sleep and daytime impact.

-

Assess severity and contributing factors and comorbidities.

-

Educate the patient on behavioral strategies and realistic sleep expectations.

-

Offer or refer for CBT-I (in person or digital).

-

Use pharmacotherapy judiciously, time-limited, and always with follow-up.

-

Reassess after 4–8 weeks to consider tapering or switching to non-pharmacological maintenance.

-

Refer to a certified sleep medicine center chronic, complicated, addicted or refractory patients. Continuous follow-up and relapse prevention strategies are crucial, as insomnia frequently recurs after stress or illness.

Concluding remarks

Insomnia is a common, underdiagnosed, and treatable disorder with significant impact on health and quality of life. Modern understanding recognizes it as an autonomous condition, not merely a symptom, capable of inducing systemic consequences if left untreated. Primary care physicians play a pivotal role in early identification and initiation of evidence-based therapy. The 2023 European guidelines emphasize: priority of CBT-I and e-CBT-I, cautious use of hypnotics, incorporation of novel agents such as daridorexant when appropriate, and the integration of sleep education into medical curricula. Promoting awareness, systematic evaluation, and multidisciplinary collaboration will help reduce the growing burden of insomnia in Switzerland and beyond.

Literature:

1 Riemann D et al.: European Insomnia Guidelines: An update on the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res 2023; 32: e14035 2 Bundesamt für Statistik (BFS): Gesundheit und Schlafstörungen in der Schweizer Bevölkerung 1997-2022. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/rm/home/statisticas/catalogs-bancas-datas.assetdetail.32306010.html ; zuletzt aufgerufen am 4.11.2025 3 Lu M et al.: Comparative Effectiveness of Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy vs Medication Therapy Among Patients With Insomnia. JAMA Netw Open 2023; 6(4): e237597 4 Dauvilliers Y et al.: Daridorexant in insomnia disorder: two randomised phase 3 trials. Lancet Neurol 2022; 21: 125-39 5 Morin CM, Buysse DJ: Management of Insomnia. N Engl J Med 2024; 391(3): 247-58

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren:

Ultraschall ist die erste Wahl in der Diagnostik

Bei der Riesenzellarteriitis ist, insbesondere wenn sie die Arteria temporalis betrifft, rasches Handeln erforderlich. Die Diagnose kann mittels Sonografie und Labor schnell gestellt ...

Osteoporose bei rheumatischen Erkrankungen

Zu den zahlreichen Komplikationen und Komorbiditäten, die mit unterschiedlichen entzündlich-rheumatischen Erkrankungen einhergehen können, zählt auch die Osteoporose. Diagnostische ...

Wann und unter welchen Bedingungen?

Patient:innen unter einer immunsuppressiven Therapie verkennen oft, wie wichtig Impfungen für sie sind. Ein Vortrag von Dr. med. Berger auf dem SGR-Kongress befasste sich mit der Art der ...