Lymph node assessment in endometrial cancer

Author:

Dr. Irina Tsibulak

Universitätsklinik für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe

Medizinische Universität Innsbruck

E-Mail: irina.tsibulak@i-med.ac.at

Vielen Dank für Ihr Interesse!

Einige Inhalte sind aufgrund rechtlicher Bestimmungen nur für registrierte Nutzer bzw. medizinisches Fachpersonal zugänglich.

Sie sind bereits registriert?

Loggen Sie sich mit Ihrem Universimed-Benutzerkonto ein:

Sie sind noch nicht registriert?

Registrieren Sie sich jetzt kostenlos auf universimed.com und erhalten Sie Zugang zu allen Artikeln, bewerten Sie Inhalte und speichern Sie interessante Beiträge in Ihrem persönlichen Bereich

zum späteren Lesen. Ihre Registrierung ist für alle Unversimed-Portale gültig. (inkl. allgemeineplus.at & med-Diplom.at)

Lymph node assessment in endometrial cancer is crucial for staging and treatment planning. It involves evaluating sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) and performing lymphadenectomy to detect metastases. Accurate assessment helps tailor adjuvant therapy, improving patient outcomes and reducing overtreatment risks.

Keypoints

-

The SLN concept is an image-guided precision surgery with enhanced pathology.

-

Less can be more: SLN mapping allows a more accurate identification of patients with nodal disease compared to lymphadenectomy.

-

Even in high-risk groups SLN mapping ensures the oncologic safety of lymphadenectomy.

-

Complete lymphadenectomy will not change management in nodal positive disease in the absence of bulky nodes.

-

To date, there is no evidence of therapeutic benefit of complete lymphadenectomy in node-positive endometrial carcinoma.

Background

In 1987, the landmark Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) Cooperative Trial 33 demonstrated, that a significant proportion (22%) of clinically presumed stage I endometrial cancers had extra-uterine spread. Following this data, pelvic and para-aortic lymph node evaluation was adopted in the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging criteria.1

To perform lymph node evaluation for uterine cancers, the anatomy of the lymphatic drainage of the uterus should be recalled. It can be classified in three pathways:

-

The broad ligament pathway, which is the most common pathway, comprising the lower uterine lymphatics draining to the pelvic nodes.

-

The infundibulo-pelvic ligament pathway, which drains via the uterine fundus to join ovarian vessels, draining the para-aortic nodal basins and terminating in the vicinity of the renals.

-

The round ligament pathway, the least common pathway, comprising the mid-uterine lymphatics, which run within the round ligament to drain to the inguinal nodal basins.2,3

The goal of lymph node assessment in apparent stage I/II endometrial cancer is to identify patients at high risk of recurrence and to tailor adjuvant treatment. Two randomized clinical trials showed no survival benefit for pelvic lymphadenectomy in patients with early endometrial carcinoma, therefore, lymph node evaluation should be seen as a pure staging procedure.4,5

In early 2010s, the concept of sentinel lymph node (SLN) was introduced in endometrial cancer, which was proven a useful and validated technique for identification of lymph nodes that are at high risk for metastases in early-stage disease. Furthermore, this technique was proved to reduce peri-operative morbidity associated with systematic lymphadenectomy.

Various tracers have been used for SLN detection in the last years: technetium-99m-labeled nanocolloid, isosulfan blue dye, and finally indocyanine green (ICG), which identified more sentinel nodes than blue dye in women with cervical and uterine cancers in the randomized phase3 FILM trial. Furthermore, no difference was seen in the pathological confirmation of nodal tissue between the two mapping substances.6 Following the FILM trial, ICG became gold standard in SLN mapping for endometrial cancer.

Diagnostic accuracy

The diagnostic accuracy of SLN technique was evaluated in the FIRES trial with 356 patients diagnosed with clinical stage I endometrial carcinoma. All grades and all histological subtypes were included in this trial. Authors reported a sensitivity of 97,2% and a negative predictive value of 99,6%. Furthermore, SLN were significantly more likely to contain metastatic disease than non-SLN (5% vs 1%, p=0,0001).7

The diagnostic accuracy of SLN exclusively in high-risk tumors was investigated in the SHREC trial. In this prospective cohort study of 257 patients with stage I/II high-risk endometrial cancer, 52 of 54 pelvic lymph node metastases were correctly identified by the SLN with a sensitivity of 98% and a negative predictive value of 99,5%. Isolated para-aortic metastases were reported in 1% of the cases.8

Sentinel lymph node algorithm and ultrastaging

However, SLN concept is more than detecting the right lymph node. A crucial step in SLN assessment is pathologic ultrastaging, which involves additional sectioning and staining of the SLN with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) to examine the SLN for low-volume metastatic disease as micrometastases and isolated tumor cells.9 The value of ultrastaging was nicely demonstrated in a study by the Mayo Clinic group. In this study, authors re-reviewed pathologic slides obtained at the time of lymphadenectomy at diagnosis and performed ultrastaging of all negative pelvic lymph nodes. Pathologic review of H&E-stained slides identified 1 patient with micrometastases in 1 of 18 pelvic lymph nodes removed. Ultrastaging of 296 pelvic lymph nodes removed from the other 9 patients identified 2 additional cases (1 with micrometastases and 1 with isolated tumor cells). Therefore, additional sectioning within ultrastaging protocol identified +30% positive pelvic lymph nodes.10

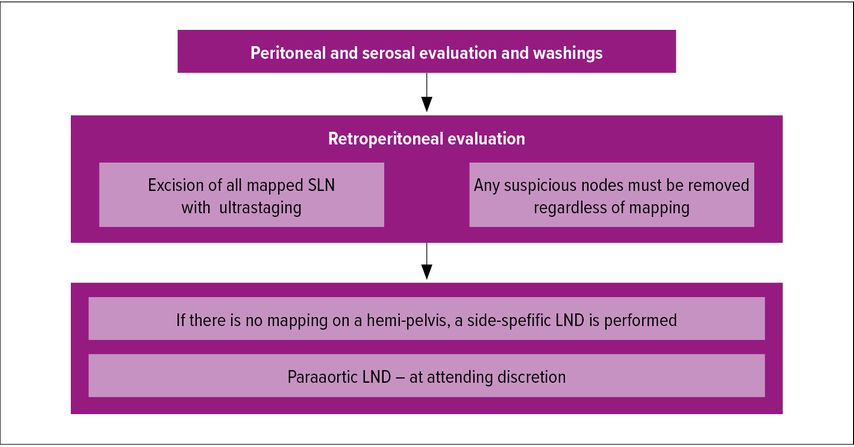

Besides ultrastaging, adherence to a structured SLN algorithm helps to reduce the false-negative rate. Such algorithm was proposed by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) group and is depicted in Figure 1.

The algorithm includes retroperitoneal evaluation with excision of all mapped SLN and their ultrastaging, as well as removal of any suspicious node and side-specific lymphadenectomy in patients with failed mapping. This algorithm was shown to reduce the false-negative rate from 23% if only mapped nodes were removed to 3% when the algorithm was applied.11

Current standard of care

Most of current guidelines support use of SLN mapping as preferred alternative to full lymphadenectomy for staging purposes in patients with endometrial carcinoma, including high-risk tumors.12,13 Of note, removal of nodes for staging purposes should be omitted in patients with apparent metastatic disease, as it will not change management.

However, the value of para-aortic staging is still a matter of debate and both ESGO and NCCN guidelines leave this step at surgeon’s discretion.

Current debate: Role of para-aortic lymphadenectomy

Para-aortic nodes may be reached via the infundibulo-pelvic ligament pathway, and there is concern that some isolated para-aortic lymph node metastases could be missed when applying SLN mapping only.3 The challenge of performing para-aortic lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer starts with the procedure itself: To date, there is no consensus on boundaries, extent, and indications of para-aortic lymph-node staging. In a survey performed by the MD Anderson Cancer Center group in 2010, 50% of board-certified gynecologic oncologists stated to define the inferior mesenteric artery as upper border of para-aortic lymph node dissection, 35% would stop between the inferior mesenteric artery and the renal vein, and only 11% would go up to the renal vein.14 Furthermore, the procedure is associated with higher complication rates and is not always feasible in multimorbid obese patients with endometrial carcinoma.

The rate of isolated para-aortic involvement was reported to be as low as 0,9% in low-risk tumors and 2,5% in high-risk subtypes.14 However, these data are from the pre-SLN era, prior to image-guided surgery and the introduction of pathologic ultrastaging, and may thus metastatic nodes in the pelvishave been missed.3 When retrospectively performing pathologic ultrastaging of patients with previously confirmed negative pelvic lymph nodes and isolated para-aortic metastases, the prevalence of isolated para-aortic metastases could be reduced from 2,5% (10/394) to 1,8% (7/394) in the previously mentioned study by the Mayo Clinic group.10 It is important to underline, that adherence to the SLN algorithm and ultrastaging of the SLN removed can further mitigate the concern of missing cases of isolated paraaortic dissemination.11

Another argument against systematic para-aortic lymph node dissection could be the pattern of first recurrence of stage IIIC1 endometrial cancer with no para-aortic nodal assessment performed. In a study from the MSKCC, isolated lymph nodal recurrences were reported in 8,3% (17/207) of IIIC1 patients with no previous para-aortic lymphadenectomy and isolated para-aortic recurrence was diagnosed in 3,9% (8/207) of patients after a median follow-up of 32 months.16

However, some would justify para-aortic staging with the results of a retrospective cohort study from Japan – the SEPAL trial. In this study, significantly longer overall survival was reported in the pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy group (346 patients) than in the pelvic lymphadenectomy-only group (325 patients) (HR 0.53, 95% CI 0,38; 0,76; p=0.0005). In a subgroup analysis, this findingswere true for 407 patients with intermediate or high-risk tumors (p=0,0009), but not in low-risk cancers.17 The validation of these findings is a matter of research in the ongoing prospective ECLAT trial by the German AGO Group. The primary objective of this study is the evaluation of the effect of comprehensive pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in the absence of bulky nodes on 5-year overall survival of patients with stages I and II and a high risk of recurrence. Study accrual should be completed in 2025 and results should be presented in 2031.18

Literatur:

1 Creasman WT et al.: Surgical pathologic spread patterns of endometrial cancer. Cancer 1987; 60(8 Suppl): 2035-41 2 Abu-Rustum NR: Lecture, ESGO Congress 20193 Eriksson AG et al.:Update on Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Surgical Staging of Endometrial Carcinoma. J Clin Med 2021; 10(14): 3094 4 Kitchener H et al.: Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): A randomised study. Lancet 2009; 373: 125-36 5 Benedetti Panici P et al.: Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008; 100: 1707-16 6 Frumovitz M et al.: Near-infrared fluorescence for detection of sentinel lymph nodes in women with cervical and uterine cancers (FILM): a randomised, phase 3, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19(10): 1394-403 7 Rossi EC et al.: A comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy to lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer staging (FIRES trial): a multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18(3): 384-92 8 Persson J et al.: Pelvic Sentinel lymph node detection in High-Risk Endometrial Cancer (SHREC-trial)--the final step towards a paradigm shift in surgical staging. Eur J Cancer 2019; 116: 77-85 9 Kim CH et al.: Pathologic ultrastaging improves micrometastasis detection in sentinel lymph nodes during endometrial cancer staging. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2013; 23(5): 964-70 10 Multinu F et al.: Ultrastaging of negative pelvic lymph nodes to decrease the true prevalence of isolated paraaortic dissemination in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2019; 154(1): 60-4 11 Barlin JN et al.: The importance of applying a sentinel lymph node mapping algorithm in endometrial cancer staging: beyond removal of blue nodes. Gynecol Oncol 2012; 125(3): 531-5 12 Abu-Rustum NR et al.: Uterine Neoplasms, Version 1.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2023;21(2):181-209 13 Concin N et al.: ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021; 31(1): 12-39 14 Soliman PT et al.: Lymphadenectomy during endometrial cancer staging: practice patterns among gynecologic oncologists. Gynecol Oncol 2010; 119(2): 291-4 15 Creasman WT: Surgical-pathological findings in type 1 and 2 endometrial cancer: An NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study on GOG-210 protocol. Gynecol Oncol 2017; 145(3): 519-25 16 Aloisi A et al.: Patterns of FIRST recurrence of stage IIIC1 endometrial cancer with no PARAAORTIC nodal assessment. Gynecol Oncol 2018; 151(3): 395-400 17 Todo Y et al.: Survival effect of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (SEPAL study): a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet 2010; 375(9721): 1165-72 18 Emons G et al.: Endometrial Cancer Lymphadenectomy Trial (ECLAT) (pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in patients with stage I or II endometrial cancer with high risk of recurrence; AGO-OP.6). Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021; 31(7): 1075-9

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren:

Postpartale Blutung im Fokus

Wenn sich die Sonne über dem Tafelberg erhebt und das goldene Licht über Kapstadt legt, ahnt man kaum, dass sich hier im Oktober 2025 mehr als 8000 Fachpersonen aus über 130 Ländern ...

Künstliche Intelligenz in der Brustpathologie

Die Einführung von künstlicher Intelligenz (KI) markiert einen Paradigmenwechsel in der Pathologie – insbesondere in der Brustpathologie. Validierte KI-Tools steigern bereits heute ...

Muss das duktale Carcinoma in situ noch operativ behandelt werden?

Das duktale Carcinoma in situ (DCIS) ist ein möglicher Vorläufer des invasiven Mammakarzinoms, wird jedoch zunehmend als heterogene Entität erkannt, sodass eine Standardtherapie mit ...